We were sitting in Barry and Kat Strathman’s living room, trying to explain a design change that, from our perspective, was a no-brainer.

They weren’t convinced. And honestly? They had every right to feel that way.

They weren’t just early buyers in East Beach, Norfolk’s ambitious urban renewal effort. They were believers. They’d attended the very first design charrette. They’d built a house when others wouldn’t even deliver a pizza to the neighborhood. And now, years later, they were finding out—secondhand—that the master plan had been changed.

Even with a well-structured stakeholder engagement strategy in place, we’d stumbled.

But we recovered. Because the real test of stakeholder engagement isn’t whether you get it perfect. It’s whether you’re willing to go back, re-engage, and do the work when trust wobbles.

Why Stakeholder Engagement Matters—From the Start

Real estate development isn’t just about land. It’s about people.

And if you don’t start your project by clearly identifying who those people are—and how to engage them—you’ll spend the rest of the process playing catch-up.

That’s why stakeholder engagement needs to start during Strategic Definition.

Who has influence?

Who will be impacted?

What are they most concerned about?

When do they need to be engaged—and how?

Get those answers early, and you can build a purposeful plan.

Miss them, and you’re building on unstable ground.

The East Beach Playbook: What Stakeholder Engagement Looks Like When It’s Done Right

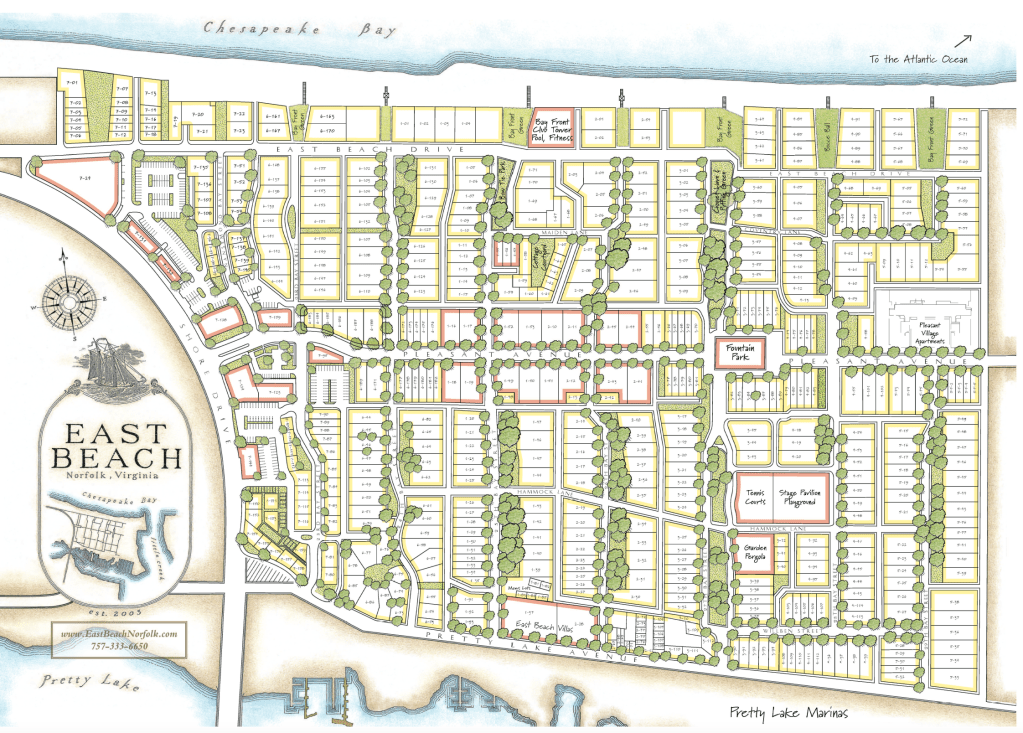

The redevelopment of East Beach wasn’t just a turnaround—it was a collaborative effort from day one. Here’s how it came together.

City Officials and NRHA

In 1993, the Norfolk City Council designated 90 neglected acres in East Ocean View as a redevelopment zone. The Norfolk Redevelopment and Housing Authority (NRHA) led the charge, with the goal of transforming a costly liability into a thriving neighborhood that could attract middle-income families and revitalize the tax base.

Community Engagement and Planning

In 1994, NRHA hosted a public design charrette led by Duany Plater-Zyberk & Co. (DPZ). This wasn’t a token meeting. Residents and stakeholders shaped the direction of the master plan—preserving dunes, softening the impact of Bay winds, and creating a neighborhood that felt both timeless and livable.

Civic Groups and Task Forces

Local groups weren’t sidelined. They were deeply involved. Their input guided land use decisions, green space priorities, and community programming—keeping the plan rooted in local values.

Real Estate Developers and the Private Sector

The East Beach Company, the private company established for the development of East Beach, worked hand-in-hand with public agencies. Together, they envisioned a mixed-use traditional neighborhood with around 700 homes, including rental units, ADUs, public amenities, retail shops, and an accessible and walkable beach.

The result?

A master-planned coastal community shaped by the vision of its stakeholders.

And yet… we still stumbled.

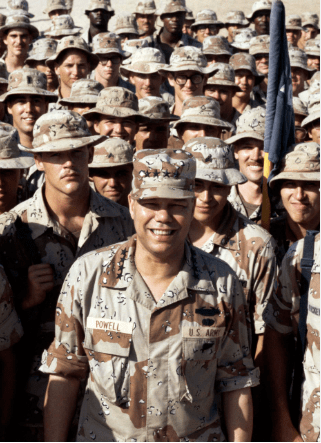

“Don’t Get Too Far in Front of Your Troops”

I first heard that phrase while listening to a radio interview about General Colin Powell. The author being interviewed said that one of Powell’s greatest strengths, even in civilian and political life, was that he never stopped thinking like an infantryman.

What does that mean?

In the infantry, you learn quickly not to get too far ahead of your own troops. If you do, one of two things happens:

- You lose your support and supplies—and eventually burn out.

- Or worse, your troops doesn’t recognize you anymore, might think you’re the enemy and try to shoot you.

That lesson hit me hard. Because I’ve seen it happen in real estate development. I’ve lived it.

Even with the best intentions—and even with the best plan—you can get out in front of your people, lose touch, and wind up creating confusion or resentment.

Which brings us back to the Strathmans.

When Good Plans Aren’t Enough: A Story of Misstep and Repair

Years after the original charrette, we introduced a few design refinements to bring more physical and visual access to the Chesapeake Bay. These were subtle but meaningful changes—ones we believed would elevate the neighborhood even further.

But we failed to bring our early champions along with us.

Barry and Kat had taken a leap of faith when no one else would. And we didn’t keep them close. We got too far ahead of our troops.

When they reached out—frustrated and surprised—we didn’t double down or get defensive.

Mike Watkins, DPZ’s lead designer and often referred to as ‘the nicest person in New Urbanism,’ came with me to their home. He explained the changes. He listened. And before we left, he gave them his personal cell number.

“If anything ever doesn’t feel right,” he said, “call me. Anytime.”

That gesture mattered. It repaired the trust—not because of what we changed on paper, but because of how we showed up.

The Core Components of Stakeholder Engagement

So how do you avoid missteps like that—and build alignment from day one?

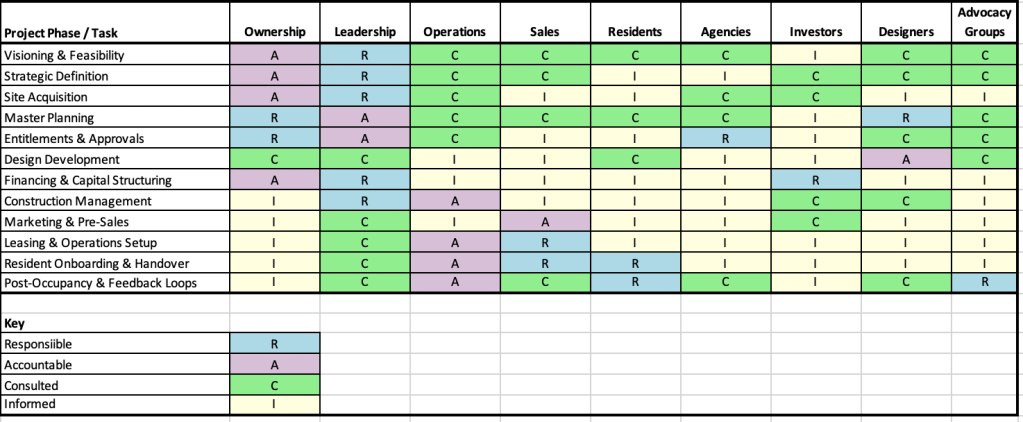

Here’s what I use with the various development teams I have worked in the past:

1. Identification of Stakeholders

Start with a full inventory—internal (ownership, leadership, ops, sales) and external (residents, agencies, investors, designers, advocacy groups). Missing someone can mean missing something important.

2. Mapping Interests and Influence

Every stakeholder brings different concerns. Some care about ROI. Others about access to parks. Get clear on what success means to each group, what are there hot buttons—and how much weight their opinion should carry.

3. Phased Engagement

Engage the right people at the right time:

- Site Analysis: Gather historical and cultural insights

- Project Visioning: Align on goals and values

- Master Planning: Consult broadly on land use and identity

- Design: Invite co-creation and operational feedback

- Pre-Construction: Coordinate with builders and regulators

- Implementation: Keep the loop open for feedback, evolution, and continuous improvement

4. Integrated Communication

Communicate frequently, clearly, and contextually. Use RACI charts to clarify who decides what and who needs to be consulted and informed. Host regular town halls. Share decisions transparently. Listen hard.

5. Evolutionary Engagement

Engagement doesn’t end at occupancy. It evolves—through governance changes, amenity updates, new products, and sustainability reviews. Keep showing up.

Your Project Needs More Than a Plan—It Needs a Pulse

Stakeholder engagement isn’t a one-and-done checklist. It’s a rhythm. And when you get that rhythm right, everyone moves forward together.

At East Beach, we had the right framework. The city, NRHA, civic groups, developers, and governmental agencies, and were all at the table from the start.

But even great frameworks need flexibility. They need humility. And they need proximity.

Because when you get too far ahead of your people, you risk losing them.

We stumbled. We corrected. And that correction—made with respect and humanity—is what turned early allies into lifelong advocates.

So don’t just map your stakeholders.

Know them.

Hear them.

Walk with them.

And stay close. Because in the end, leading from the front isn’t about charging ahead.

It’s about making sure your people are right there with you.

Leave a comment