How One Architect’s Ideas—and One Formative Year—Shaped My Life

I was saddened to see so many posts from fellow CNUers and New Urbanists announcing the passing of Leon Krier, an urbanist, architect, theorist, educator, and mentor. For those who don’t know him, Leon wasn’t known so much for the buildings he designed but for the ideas he championed. And in my case, he was someone who changed the way I saw the world and, ultimately, what I decided to do with my life.

Krier believed cities should be designed for people, not cars. Beauty is not a luxury but a human right. That scale, proportion, and public space matter. He had no patience for the alienating sprawl of postwar planning or the soulless abstractions of high modernism. Instead, he looked backward to move forward, drawing from centuries of accumulated wisdom to shape more humane, enduring, and walkable towns.

He called out the moral dimension of architecture and urban design. He made one question not just how we build but why. And for me, all of that clicked in a powerful way during my third year at the University of Virginia’s School of Architecture.

The Aligning of the Stars – A Least for Me

Looking back, the stars really did seem to align that year.

Leon Krier was a visiting professor teaching at a graduate design studio. I wasn’t in his studio, but I attended his lectures and tried to sit in on every jury for his design studio that I could. He spoke with clarity, purpose, and a level of conviction that cut through the typical academic fog.

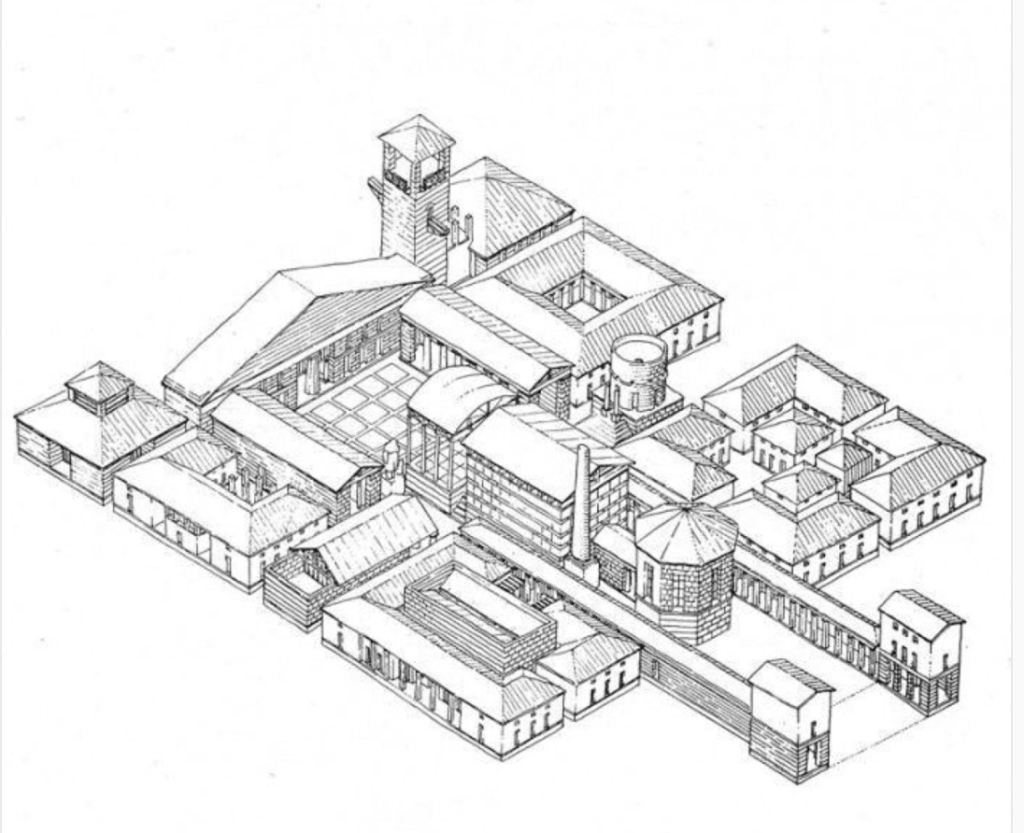

I started reading everything I could get my hands on by him. His words, diagrams, and drawings were elegant and deceptively simple. His arguments had weight. His drawings had meaning. One piece in the article, a write-up of a debate between Krier and Peter Eisenman from the late 1970s, stuck with me. In it, Krier provided an overview of his design for a school in Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines. Rather than a sleek modernist object, he designed it like a traditional village, broken down into buildings around streets and squares.

Eisenman dismissed it outright. “Leon, you’re a madman,” he said. “You can’t build like this today.”

Krier didn’t flinch. “You can’t. But I can.”

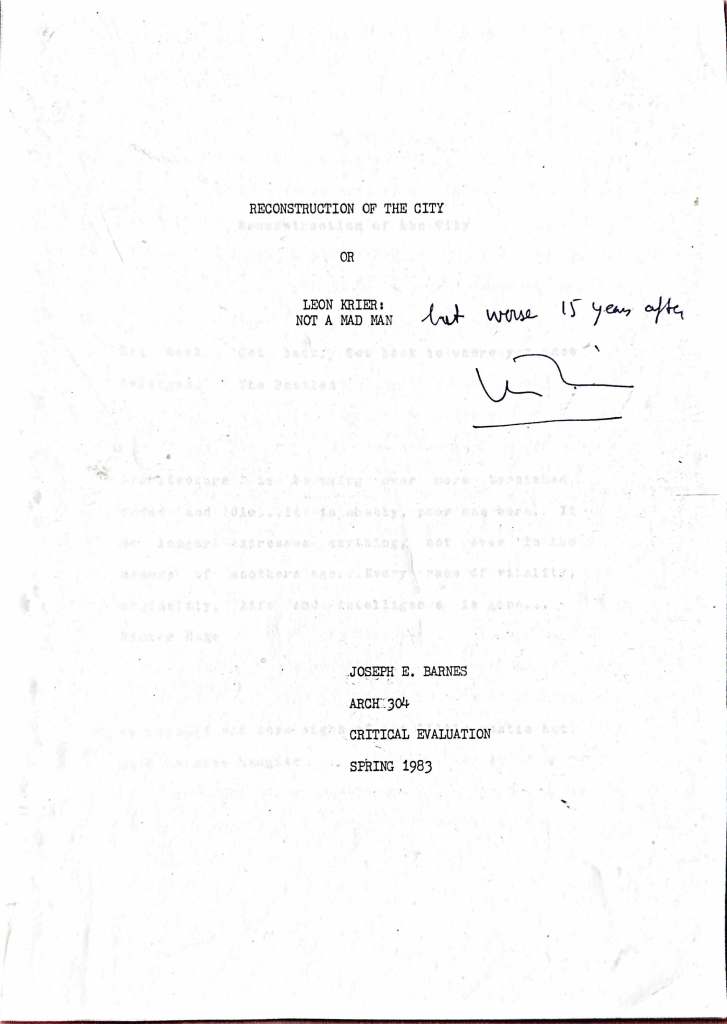

That stuck with me. I used that debate as the basis for a paper I wrote my Critical Evaluation class taught by Bruce Abbey. I titled the paper:

“RECONSTRUCTION OF THE CITY

OR

LEON KRIER: NOT A MAD MAN”

The opening paragraph read:

“The design of the School at St. Quentin-en-Yvelines is not the product of a fanatical madman whose mind is filled with regressive visions of plunging the world of architecture back into the darkness of Middle Age design and building technology. Rather, St. Quentin is the product of a man with progressive visions and a keen desire to regain the ideals of urban life present in the pre-industrial city and before the rise of Modern Architecture.”

That paper set me on a course that led to a 30-year career centered on creating places that respect regional culture, serve daily life, and build long-term social, environmental, and economic value. It was the start of a professional worldview I carry with me to this day.

Jacquelin Robertson – Classical Roots, Forward Thinking

Leon Krier wasn’t the only influence that year.

Jacquelin Taylor “Jacque” Robertson was our Dean. His presence shaped everything at UVA’s School of Architecture. He brought gravitas, clarity, and conviction. You could feel it in every school-wide talk, every guest speaker he invited, and every conversation in Campbell Hall.

Robertson believed in architecture rooted in history. Not as nostalgia but as a thoughtful evolution. He often spoke of classical architecture as “the symbolic hard currency of the profession,” comparing it to “gold in the bank.” He urged us to understand the order of the whole, not just the parts. His thinking was grounded in civic purpose and cultural continuity, and he constantly pushed students to consider how buildings shape public life.

Under his leadership, UVA became a national platform for architectural debate and urban leadership. He brought in figures like Krier not just to critique modernism but to give us alternatives. He wanted students to engage with fundamental ideas, real cities, and real responsibility.

Robertson himself was a proponent of New Urbanism and New Classical Architecture but with a distinctly American inflection, practical, civic-minded, and rooted in the design of whole places. He believed deeply in the power of tradition to guide contemporary work. He balanced rigorous discipline with a generosity of spirit that made us feel like we were part of something bigger.

He also brought professional experience into the studio in a way that few academic leaders did at the time. He had been the first director of the Mayor’s Office of Midtown Planning and Development under John Lindsay in New York and a partner at a leading architecture firm. So, when he talked about the intersection of policy, design, and the built environment, it wasn’t theory. It was an experience.

Fast forward to 1993, when I was part of the Celebration Design and Development Management team. Robertson’s firm, Cooper Robertson and Partners, along with Robert A.M. Stern Architects, served as the master planner for Celebration. While I was technically the client and he was the consultant, we both knew the truth: I was still his student, and he was still my Dean.

Working with him years later was surreal, in the best way. What I had first absorbed as a theory in school became real on the ground. His insistence on order, clarity, and civic legibility informed everything we tried to do at Celebration. That experience brought my education full circle and reminded me of just how far one mentor’s vision can carry.

Andres Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk – A Turning Point in How I Saw the Built Environment

Next in line, in terms of the memorable and influential that year was Andres Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk (DPZ). They came to give a lecture on Seaside, Florida, which they had designed for Robert Davis on 80 acres of family-owned land in the Florida Panhandle.

Seaside was the first built example of New Urbanism, a movement advocating for walkable, mixed-use communities based on traditional town planning. Its tight street grid, front porches, public realm focus, and architectural code became influential across the U.S. and internationally. Seaside is often credited with launching a new conversation about how towns and neighborhoods could be designed to foster community. Seaside is perhaps the influential 80 acres in the history of urban design.

I had never seen a lecture by an architect like theirs. Andres and Liz didn’t show single buildings. They talked about towns, street networks, civic spaces, porch culture, and benchmarks from small Southern cities. Their slides were of the public realm, not architectural form. They opened a door for me, illustrating the deep and lasting impacts that architects can have if they focus not just on an individual building but on the entire context in which the building sits and how it impacts and can be impacted by its surroundings.

Fast forward again to two community development projects where I served as General Manager: I’On in Mount Pleasant, SC, and East Beach in Norfolk, VA, both designed by DPZ. Again, even though I was technically the client and they my consultant, I knew the pecking order of things. On a side note, the homesite my family eventually purchased in I’On to build our home, we bought from Andres, who originally received it as part of his fee for designing I’On.

Mayor Joe Riley – The Power of Civic Design and Civic Heart

Another pivotal moment that year came when Mayor Joseph P. Riley Jr. visited UVA to speak to the architecture students. At the time, I wasn’t expecting much. I’d barely heard a politician speak in person before, and I figured we’d get 50 minutes of policy, budgets, and municipal jargon.

But that’s not what happened.

What we heard instead was a masterclass in moral leadership. Riley spoke not about politics, but about place. About dignity. About beauty as a birthright, not a privilege. And about how cities, when designed with care, can elevate everyone they touch.

One story he shared that day, and which I’ve heard him tell several times since, has always stuck with me. He was at a cocktail reception in Charleston when a woman working with the catering team approached him. She thanked him sincerely for helping her family get a home. Not a housing project. A home.

At the time, Charleston was under pressure from the federal government to build more affordable housing. As often occurs in many cities, the expectation was that this would take the form of large, monolithic housing projects that too frequently became magnets for poverty, isolation, and decline.

But Riley resisted.

Instead of building projects, he pushed his team to design and build homes. Real homes on real streets that followed the same character, pattern, and urban form that defined historic Charleston. These weren’t second-class buildings hidden out of view. They were woven into the fabric of the city.

He said it wasn’t until that conversation with the catering staffer that he fully grasped the depth of what that decision meant. He asked her where she and her family lived. She didn’t say the “New Projects.” She gave a specific borough, street, and house number.

That answer, that ordinary, proud answer, carried everything he was trying to accomplish. Because it wasn’t just a place to live. It was a place of dignity. It was a place of belonging.

When Riley shared that same story during his J.C. Nichols Prize acceptance speech years later, I watched a room full of hard-nosed, ROI-driven developers wipe tears from their eyes. It was that powerful.

That’s the kind of leader Joe Riley was and still is through his leadership of the Mayors’ Institute on City Design. A mayor who understood that design is not just about materials or budgets. It’s about justice. It’s about memory. And it’s about the invisible architecture of self-worth.

The last time I saw him was at Broad Street Barber. I had my eyes closed while getting a haircut when I heard a very familiar voice over the buzz of the clippers. I opened my eyes, and sure enough, it was Joe Riley. After his haircut, I walked over to reintroduce myself and thank him for what he had done for Charleston and for the impact he had on my career. It was full circle again.

The Common Thread

There’s a common thread among these encounters that happened that seemingly magic year: Krier, Robertson, DPZ, and Riley.

- They each believed that the form of our cities shapes the character of our lives.

- They believed in civic design, not as a theory but as a tool for dignity, culture, and connection.

- They rejected placelessness and postwar sprawl.

- They made us believe that design, done well, could elevate the human experience.

- They found their way to UVA, and into my life, at the exact moment I was ready to hear and learn from them.

One final story.

It was 1997. I was serving as Celebration’s Town Architect, overseeing the design review process and frequently leading tours for visiting architects, planners, journalists, and public officials. One day, Leon Krier himself is on the tour.

To say I was nervous is an understatement. Here was the person whose ideas helped shape my professional path, walking around Celebration with me, critiquing and discussing its streetscapes, parks, and architecture.

During the walk, I called my wife, B.J., and asked if she could bring down the old college paper I had written about Krier. She showed up, our son Harry in tow, just as we reached the playground at Long Meadow.

I handed the paper to Leon. He flipped through it, smiled, and signed the cover. Right next to my title—“Not a Mad Man”—he wrote:

“But worse 15 years after.”

That signed paper remains one of my most treasured professional artifacts.

Looking back now, it’s clear that sometimes, being in the right place at the right time really can change your life. That third year at UVA lit a fuse. The people I encountered, the ideas I wrestled with, and the examples I was shown came together to form a foundation I still stand on today.

So, thank you, Leon Krier, for your presence, your persistence, and your unwavering belief in the power of design to make the world more beautiful, humane, and whole.

I’m glad you were a “Mad Man” after all.

You might be gone, but your legacy lives on in all the people and places you influenced.

Leave a comment