East Beach in Norfolk, Virginia, was envisioned as both a catalyst and a showcase for the city’s ambitious “Come Home to Norfolk” campaign. Norfolk, founded in 1682, has numerous sections containing rich urban histories, with centuries of maritime commerce, military presence, and cultural life shaping its identity. But by the early 2000s, it had been decades since the city had undertaken anything on the scale and ambition of East Beach.

At roughly 100 acres, East Beach became the largest single community development initiative in Norfolk’s history. Its success was more than a matter of real estate. East Beach was a linchpin in the city’s broader revitalization strategy, testing whether Norfolk could reclaim its tradition of building enduring, character-rich neighborhoods in an era dominated by mass-market housing.

From the outset, the Norfolk Redevelopment and Housing Authority (NRHA) made its expectations explicit. East Beach would not be another cookie-cutter subdivision dominated by large merchant builders turning out standardized floor plans. The directive was clear: every home would be custom-designed and built, each contributing to a cohesive architectural vision while reflecting the individuality of its owner. East Beach would require a higher level of craftsmanship, architectural variety, and attention to proportion than what was typical in the region’s housing market at the time.

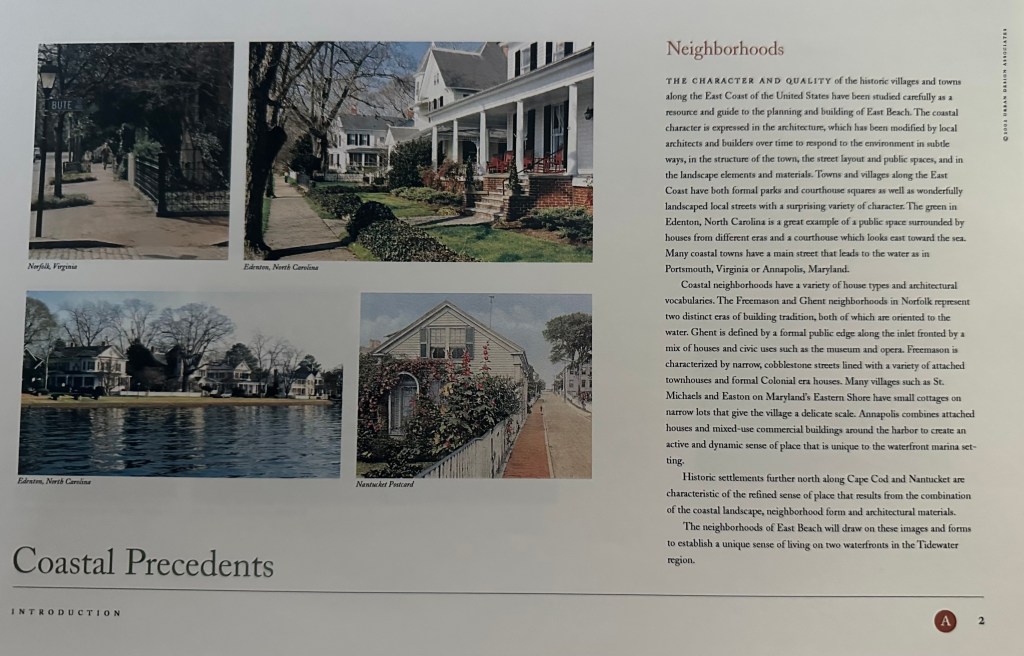

The NRHA’s reasoning was grounded in history. Norfolk has several strong precedents for good urbanism and architecture in neighborhoods like The Hague, Ghent, and Freemason. These historic districts, built before World War II, are masterclasses in human-scaled streets, regionally appropriate building styles, and finely tuned details. Brick sidewalks, deep porches, operable shutters, and tree-lined streetscapes work together to create neighborhoods that remain as desirable today as when they were built.

By contrast, much of Norfolk’s post-war housing stock, like many American cities, was shaped by Levittown-inspired development patterns: these prioritized speed, efficiency, and uniformity over architectural variety and urban character. Interiors were often well-equipped, but the exteriors lacked the charm, craftsmanship, and regional authenticity that define Norfolk’s older neighborhoods.

Many of the designs came straight from mass-produced house plan books—the kind sold in the checkout aisle of a grocery store or from the work of a local draftsperson producing plans to meet a budget, not a broader vision. These plans rarely took cues from the Chesapeake Bay region’s rich architectural traditions or the qualities that make a neighborhood feel timeless. Without guidance, there was no guarantee that the builders would produce homes consistent with the aspirations for East Beach.

East Beach’s mission was to reverse that trend. It would reintroduce the architectural integrity, walkable street patterns, and sense of place that had once been Norfolk’s hallmark. The goal was not nostalgia but rather to apply timeless design principles to meet modern needs and prove that new development could match and rival the city’s most beloved historic neighborhoods.

From my experience at Celebration, I knew you cannot simply hand out a set of design guidelines and expect the vision to build itself. Even the best-intentioned builders often face competing priorities such as speed to market, cost control, and perceived sales appeal that can dilute architectural quality. Left on autopilot, these pressures tend to produce houses that check the boxes but fall short of creating a truly memorable place.

East Beach demanded more. If we were to deliver a neighborhood with the authenticity, character, and long-term value we envisioned, we had to do more than write rules. We had to “Design in Good Design.”

For the East Beach Development Team, that meant being directly involved from day one. We engaged with builders early to inspire them with possibilities, not just to review their designs. We talked about proportion, scale, and the subtle details like column spacing, trim profiles, and window placement that give architecture its sense of rightness. We studied regional precedents together so they could see how historic homes in Norfolk’s best neighborhoods had stood the test of time.

But this wasn’t about lecturing. It was about building a shared vision and working side-by-side to bring it to life. We created an iterative, hands-on process where designs evolved through conversation, sketches, and mutual problem-solving. Builders weren’t just checking compliance boxes. They needed to shape homes that would strengthen the streetscape, complement their neighbors, and collectively form a neighborhood people would fall in love with.

Our measure of success wasn’t just how each house looked on its own, but how all the houses worked together to create streets with rhythm, variety, and a human scale. The goal was not just a collection of good houses. Our goal was to craft a great neighborhood.

Educate:

As we did at Celebration, we used the South Carolina Lowcountry as our base for the East Beach Builders Orientation. We gathered at a hotel in Mount Pleasant, where the morning session focused on helping the builders fully understand the vision behind East Beach before they ever put pencil to paper.

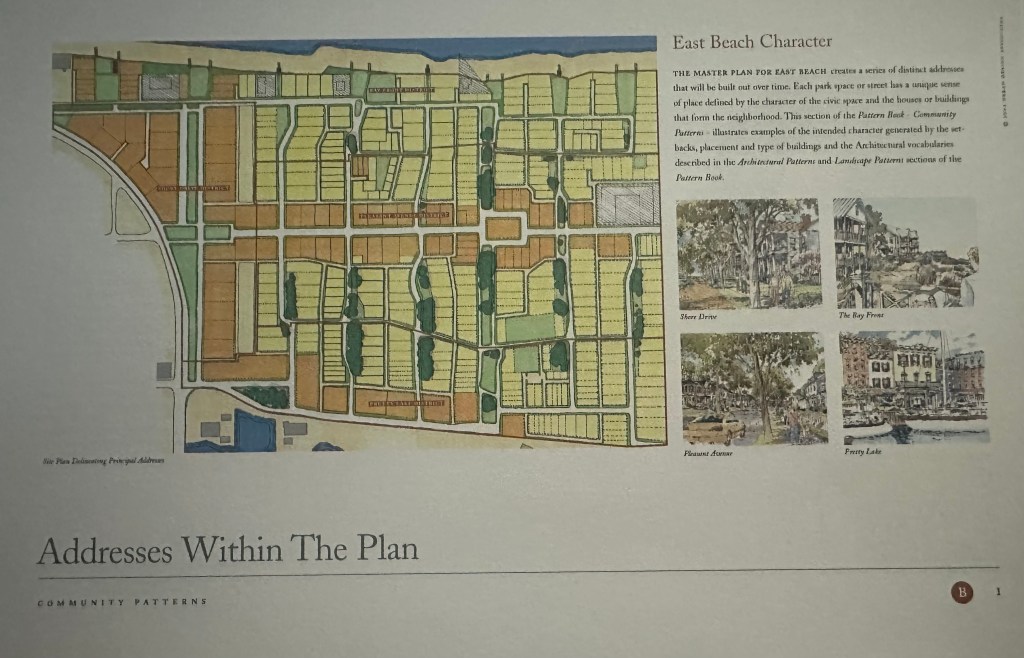

We began by walking them through the master plan, explaining how the blocks were arranged and why the north-south streets were designed to terminate with a visual reward of a framed view of Pretty Lake Marina or a Bayfront Green or pedestrian path leading directly to the Chesapeake Bay. We showed them how these greens and paths pulled water views deep into the neighborhood, creating a constant awareness of the proximity and access to the Chesapeake Bay, even for residents far from the shoreline.

We also explained one of the master plan’s more subtle but essential moves: shifting the streets by half a block. The grid shift allowed the mature trees, which once sat behind structures, to become part of new linear parks running parallel to the streets. In front of the new homes, these shaded greenways created an immediate sense of maturity and place that most new neighborhoods lack.

From there, we walked them through how the street sections and details evolved as you moved from East Beach’s more urban edges toward the relaxed, informal areas closest to the water. This transition wasn’t accidental. It was a deliberate layering of urban design principles to give the community variety and coherence.

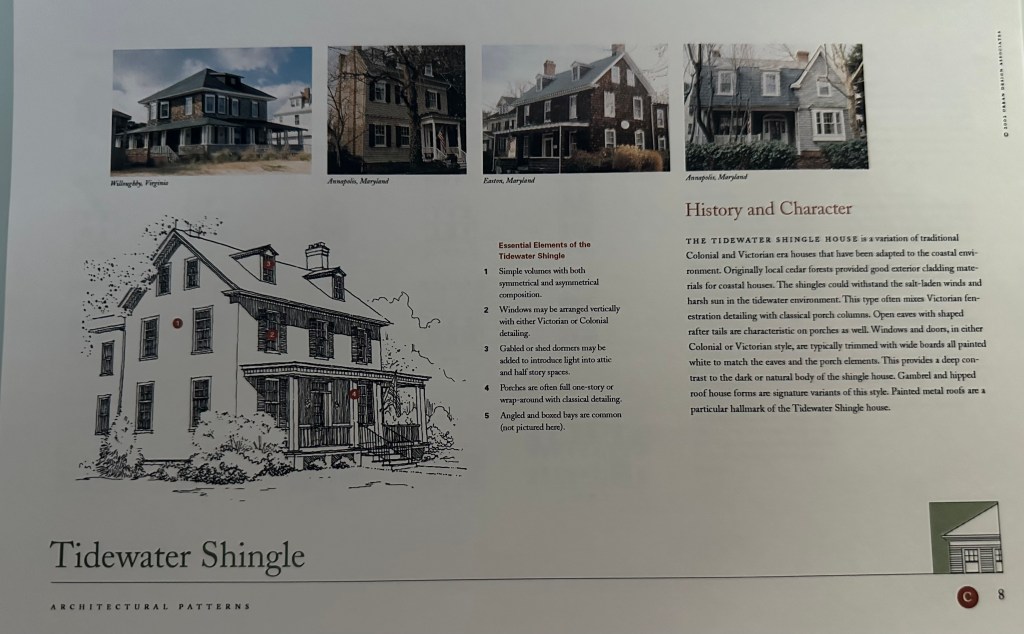

Next, we introduced the four architectural languages defining East Beach: Tidewater Colonial Revival, Tidewater Victorian, Tidewater Arts and Crafts, and Tidewater Shingle. Each was rooted in the region’s historic architecture. We outlined the essential design elements for each style, such as roof forms, porch types, window proportions, and siding materials. We discussed where each language was most and least appropriate within the master plan.

We followed Simon Sinek’s mantra throughout the session: “People don’t buy what you do; they buy why you do it.” The goal was to ensure that every builder left the room with a clear understanding of not just the “what” and “how” of East Beach’s design vision but also the “why” that gave it meaning.

Inspire: Touring Precedents

The next step in the Builders Orientation was to get out and see some outstanding work. By the early 2000s, there were far more examples to study than we had during the Celebration Builders & Architects Tour in 1995. Several new neighborhoods and villages had not only broken ground but reached a level of completion where the quality, richness, and variety of the design could be experienced first-hand.

As with Celebration, we started with the historic districts of Mount Pleasant and Beaufort, along with Newpoint. We also added Habersham in Beaufort, being developed by Bob Turner, who had played a key role in both Newpoint and I’On itself in Mount Pleasant, which was being developed by Vince Graham, also of Newpoint, along with his father, Tom, and brother, Geoff. During its formative stage, I had served as General Manager of I’On for three and a half years, so this visit felt personal.

Like what we saw with the Celebration builders visiting Newpoint years earlier, you could almost watch the light bulbs go on in their heads. The builders began to see the incremental value our design philosophy could bring in aesthetics, market appeal, and long-term value creation.

One moment, which I initially viewed as a potential problem, became one of the most effective inspirational tools of the trip. I had always considered the Builders Orientation to be a serious work trip. We planned the two-day event for a Thursday and Friday, and I expected builders to come ready to focus. So, when Roger Wood, East Beach’s Town Architect and Guild Manager, told me several builders had decided to bring their wives and turn it into a long weekend getaway, I was not pleased. In my mind, this was not a family vacation.

Roger convinced me otherwise, and we arranged for a larger bus to accommodate everyone. Ultimately, allowing the spouses to join us was the best decision we made. As we toured Newpoint, Habersham, and I’On, walking past beautifully designed, well-crafted homes, I overheard several wives quietly ask their husbands why they didn’t build houses that looked as nice or felt as special. That subtle nudge, a mix of admiration and gentle challenge, may have been the most powerful motivator. Sometimes, the best push toward better design comes from outside the meeting room.

Collaborate: The “Design Connection”

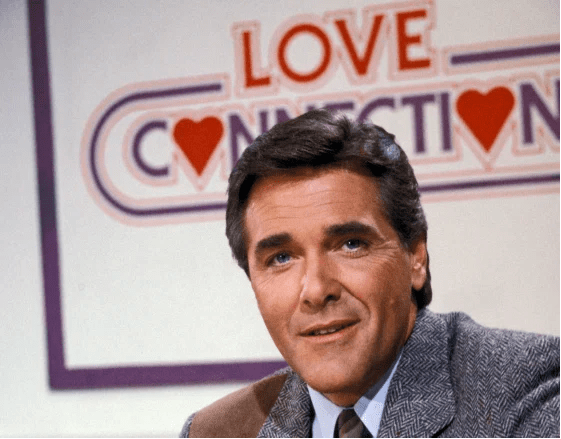

Like at Celebration, the East Beach builders weren’t used to working with top-tier design professionals to create their houses. To change that, we introduced an exercise I called “Design Connection,” modeled after the TV show Love Connection hosted by Chuck Woolery. On the show, the producers would pay for the first date between two singles. In our case, we were “paying” for the first date between an architect and a builder.

Here’s how it worked.

We invited a group of architects who had done much of the standout design work in places like I’On, Habersham, and Newpoint and had deep experience working with custom home builders. These included well-regarded firms like Moser Design Group, Allison Ramsey Architects, Don Powers, and Historical Concepts.

We pre-selected a set of floor plans, many drawn from the portfolios and plan books of these invited architects, that would fit East Beach homesites. Then we put together “design tool kits” for each team: tracing paper, pencils, markers, scales, and straightedges.

The matchmaking process was simple. We put the builders’ names in one box and the architects’ names in another. We drew one builder and one architect, paired them up, and handed them one of the pre-selected floor plans, a design kit, and a copy of the East Beach Pattern Book.

They had two and a half hours to create a façade design that met our design guidelines and that the builder felt they could build at a reasonable cost with their usual tradespeople.

At the end of the session, like a design jury in architecture school, each builder–architect team pinned up their work and presented it to the group.

Some key takeaways stood out:

- Builders realized that working with a good architect wasn’t intimidating or awkward.

- The architects added tremendous value to the process.

- Creating an appropriate, high-quality design was faster, easier, and more enjoyable with the right design partner.

When it came time to start actual house designs for East Beach, many builders continued working with the architect we had been paired them with during “Design Connection.” Not surprisingly, those who did were far more successful than those who didn’t.

To close out the Builders Orientation, we organized an oyster roast on the evening of the second day at the Creek Club in I’On. It was a relaxed, social setting, but it served a very practical purpose. Alongside the East Beach builders and the residential architects, they had worked with during “Design Connection,” we also invited several members of the I’On Builder’s Guild. This gave the East Beach builders the chance to ask candid, builder-to-builder questions about preferred materials, reliable suppliers, and the lessons learned on the ground, both good and bad.

The informal conversations that night were just as important as the structured sessions. Builders walked away with real-world insights, peer validation, and a stronger sense that what we were asking them to do at East Beach was not only possible but achievable.

Up Next:

The final article in this series, Designing in Good Design: Why the Process Matters as Much as the Product, looks at the big picture and what these experiences taught me about why great neighborhoods succeed or fail, and why process is the deciding factor.

Leave a comment