Understanding the Shift from Strategic Definition to Design Brief

During the Strategic Definition stage, the work is largely inward-facing. You’re building internal alignment. The primary audience consists of the developer, the landowner, and investors, who are the decision-makers who need to understand the project’s potential, risks, and underlying rationale.

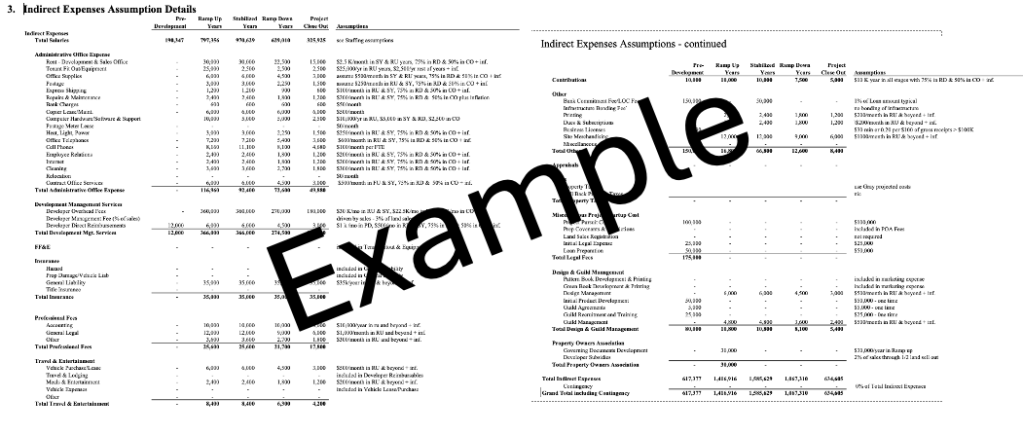

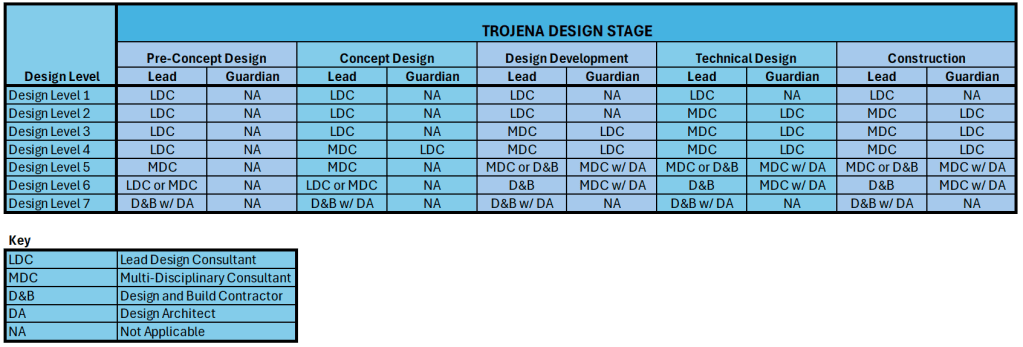

It’s about defining the vision, identifying constraints, and deciding whether to proceed. By the time you reach the Design Brief, though, the focus shifts. Now, you’re speaking to an external team. Architects, engineers, landscape designers, planners, and other consultants who weren’t in the room earlier but are now responsible for bringing the vision to life.

That shift in audience makes clarity essential. You can’t assume the design team is familiar with the backstory. Your design team needs the distilled version with just the right amount of context to understand where the project is headed and what they’re working with. That’s where the Project Overview and Site Context sections of the Design Brief come in. These sections don’t need to be lengthy, but they must be clear, well-structured, and purposeful.

Project Overview: Setting the Tone

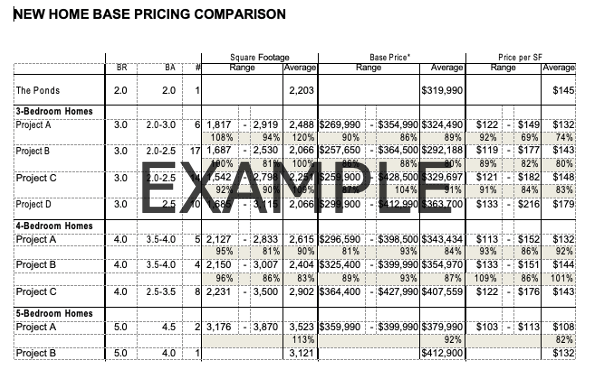

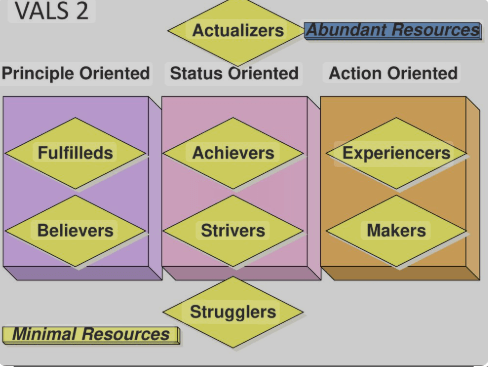

The Project Overview sets the tone. It should open with a concise articulation of the project’s vision. It is not marketing language but a grounded statement of intent. What are you trying to create, and why? The project’s vision may include the community type, the intended market segment, and the broader mission.

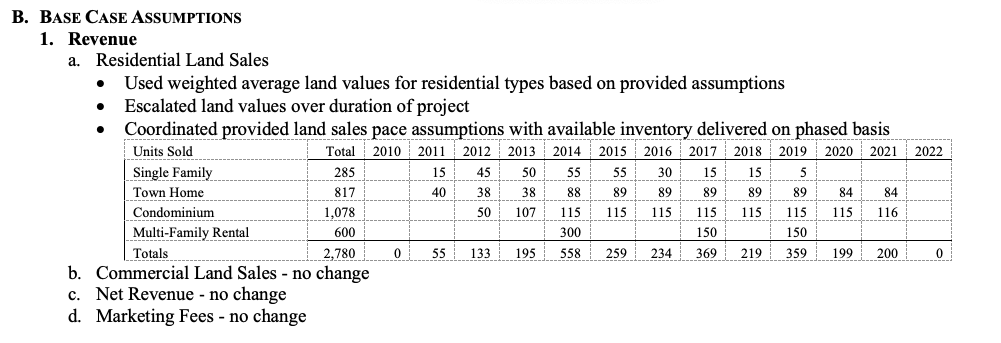

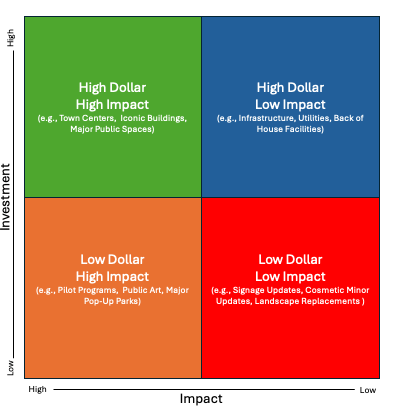

Next, outline the project goals. These can include physical goals (such as walkability or open space preservation), key financial objectives (such as returns or phasing strategies), and operational ambitions (like long-term stewardship models). It’s helpful to include a paragraph that frames the big picture and how this project fits into a larger strategic context, how it connects to the surrounding region, or what makes it different.

A well-structured Project Overview might include:

- A clear statement of vision and intent

- Core project goals: physical, financial, and operational

- Intended user or market segment

- Strategic context and positioning

- Summary of key project drivers and rationale

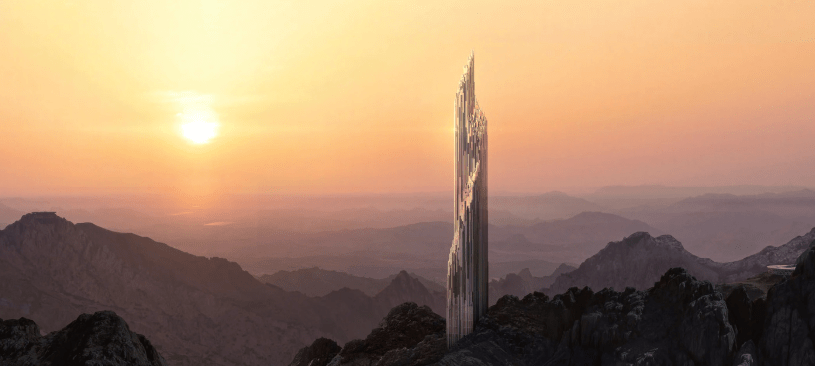

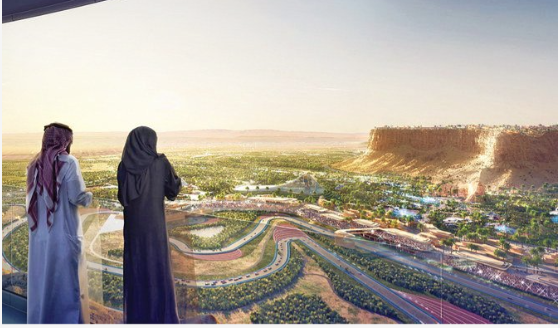

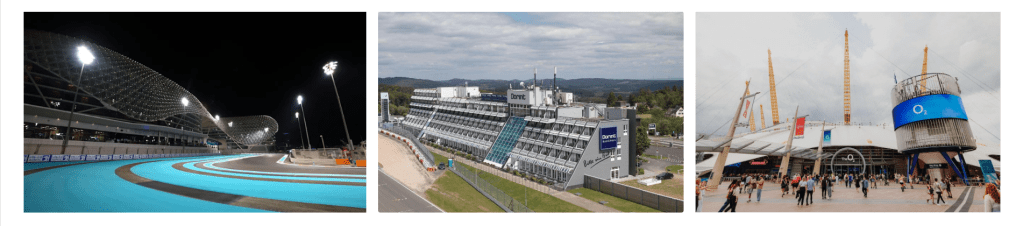

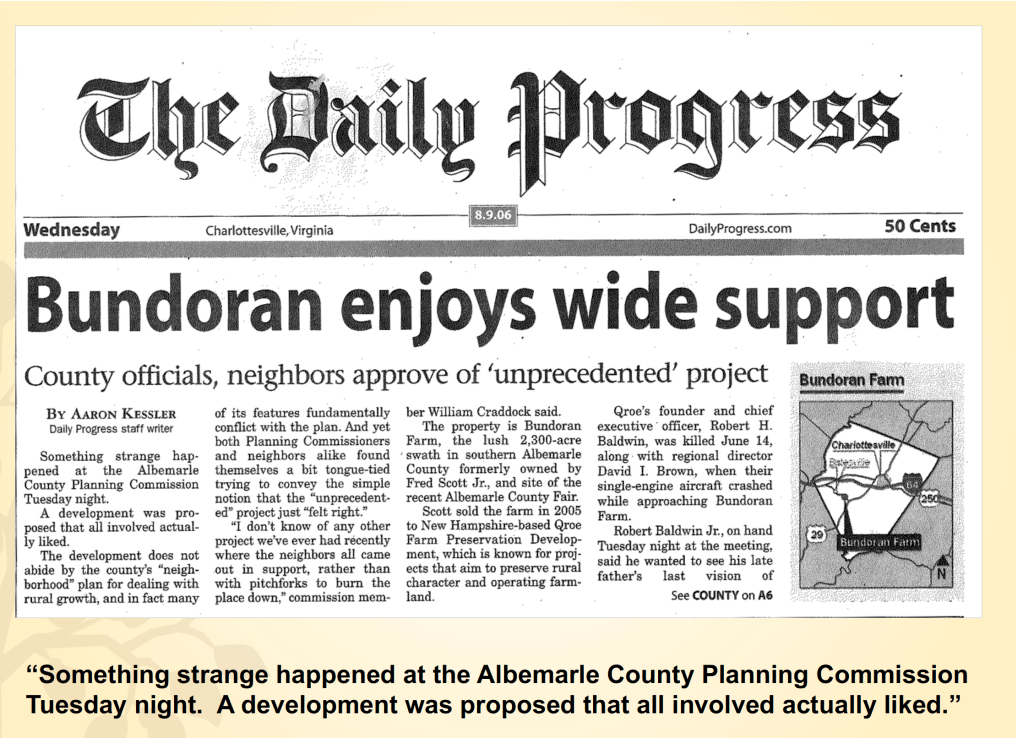

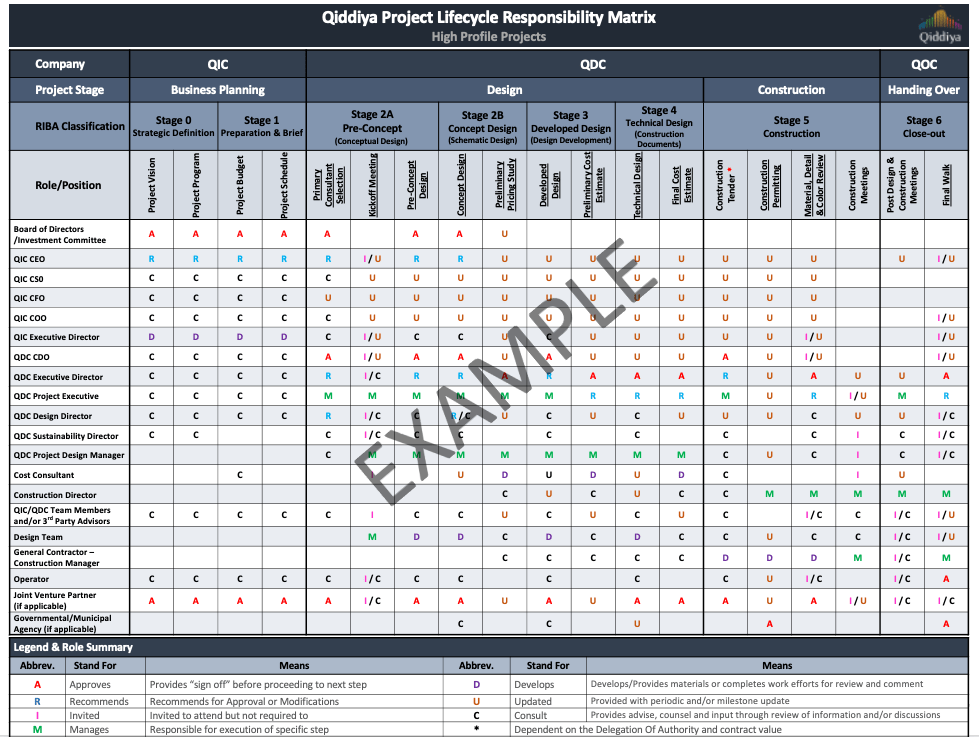

In some cases, such as Qiddiya, the Project Overview went beyond project-specific goals to include national strategic objectives. When I was serving as Acting Executive Director of Planning & Design for Qiddiya, it became immediately apparent during my early job interviews in Riyadh that this was not just another real estate project. Qiddiya is a cornerstone of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, a national strategy designed to diversify the economy, reduce oil dependence, and reshape the Kingdom’s global image.

The developer of Qiddiya, the Qiddiya Investment Company, is positioning Qiddiya as the cultural, sports, and entertainment capital of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, with a projected budget of $9.8 billion and a master plan covering 334 square kilometers. Its scope encompasses over 400 individual facilities, including theme parks, water parks, motorsports venues, concert arenas, retail districts, and housing developments. As one of the Kingdom’s flagship giga-projects, Qiddiya aims to:

- Drive economic diversification by repatriating local entertainment spending

- Generate approximately 17,000 jobs and reduce regional unemployment

- Encourage cultural transformation and broader social reform

- Enhance the quality of life for Saudi citizens

- Shift international perceptions of the country through bold, visible transformation

In essence, Qiddiya is more than an entertainment complex. It’s a strategic move to modernize society, redefine the Kingdom’s international identity, and establish a new economic engine centered on leisure, culture, and innovation.

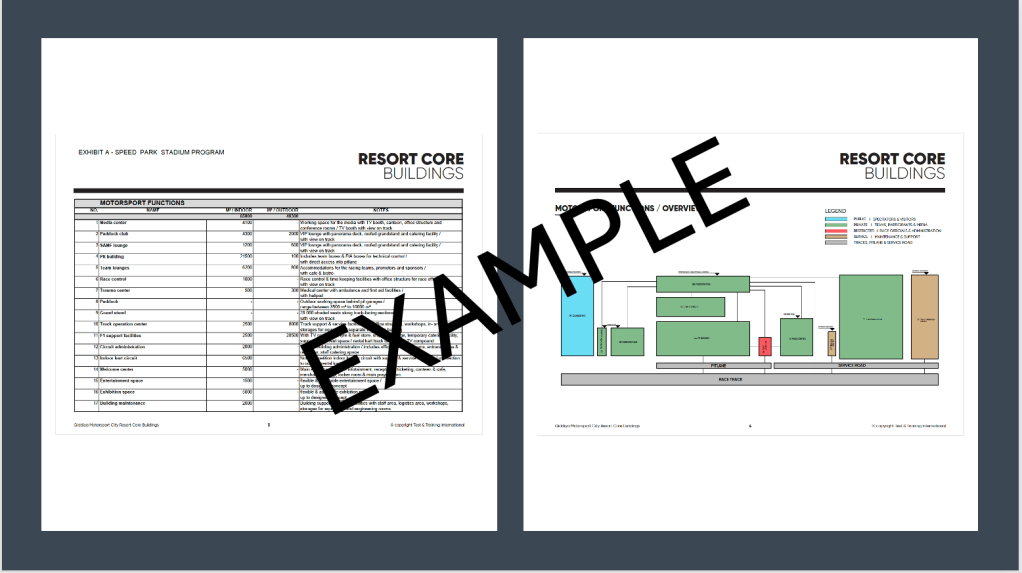

While at Qiddiya, I was responsible for organizing and managing an international design competition involving 20 globally renowned architectural firms for 12 of Qiddiya’s iconic assets, which included a Grand Mosque, multiple sports venues, an F1 track, and a stadium.

These efforts required the development of comprehensive design briefs for each asset, the selection and procurement of various design firms, the engagement of relevant development team members and subject matter experts, and the continual interface with the design firms throughout the design competition.

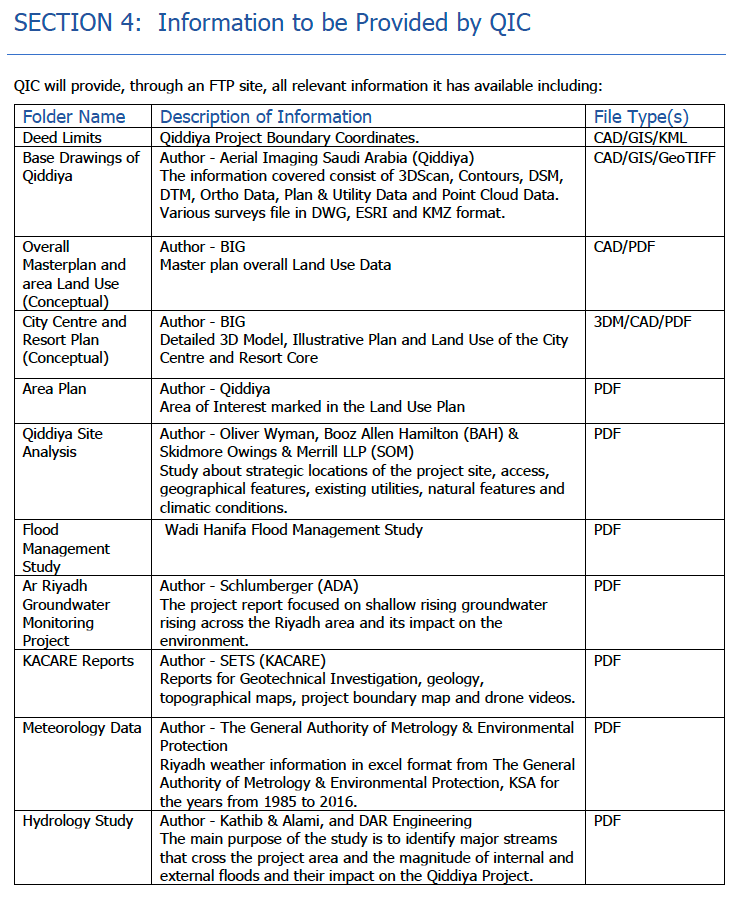

Given the importance of the project, the challenges with the site, and the short competition timeframe, we placed a strong emphasis on making sure all the participants in the competition were well-informed and equipped about both the overall vision and the unique characteristics of the site to provide an even playing field and set them up for success.

Site Context: Grounding the Vision

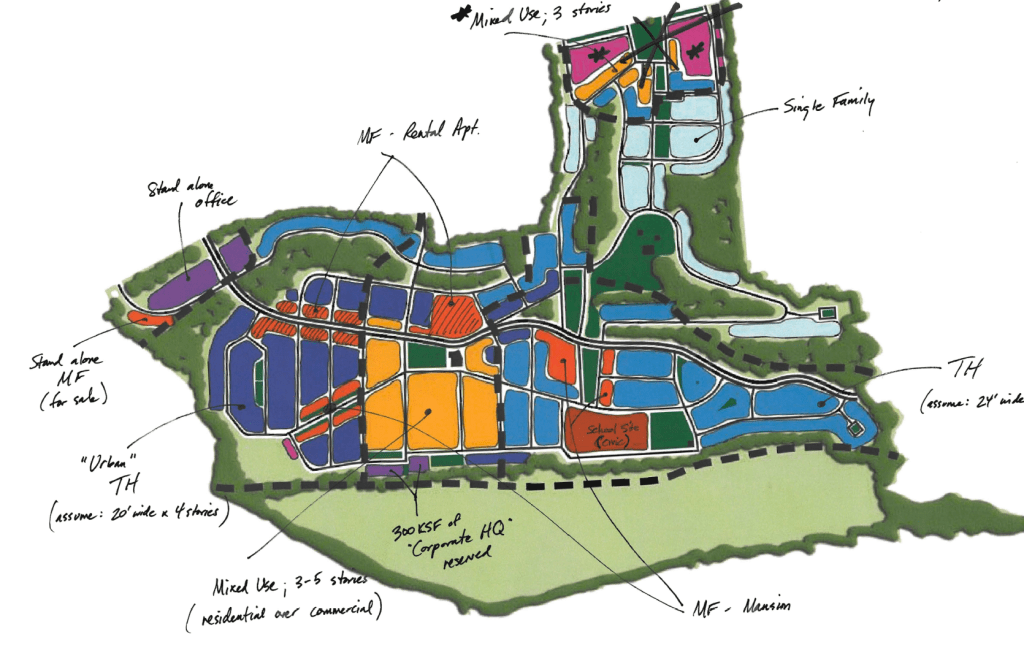

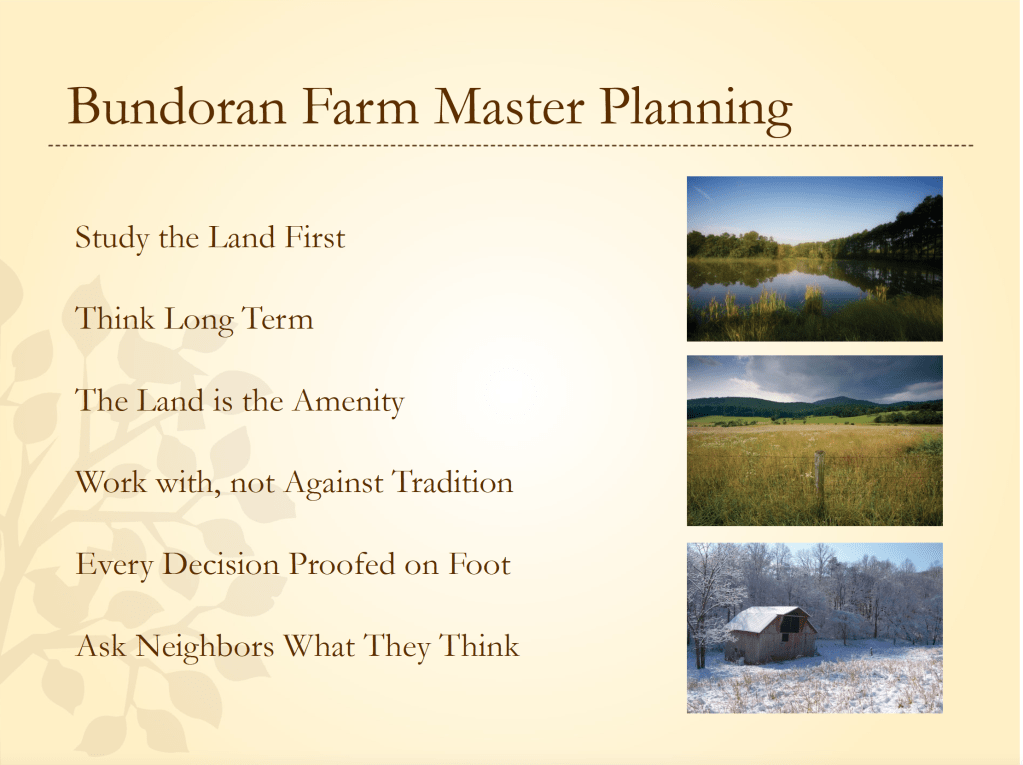

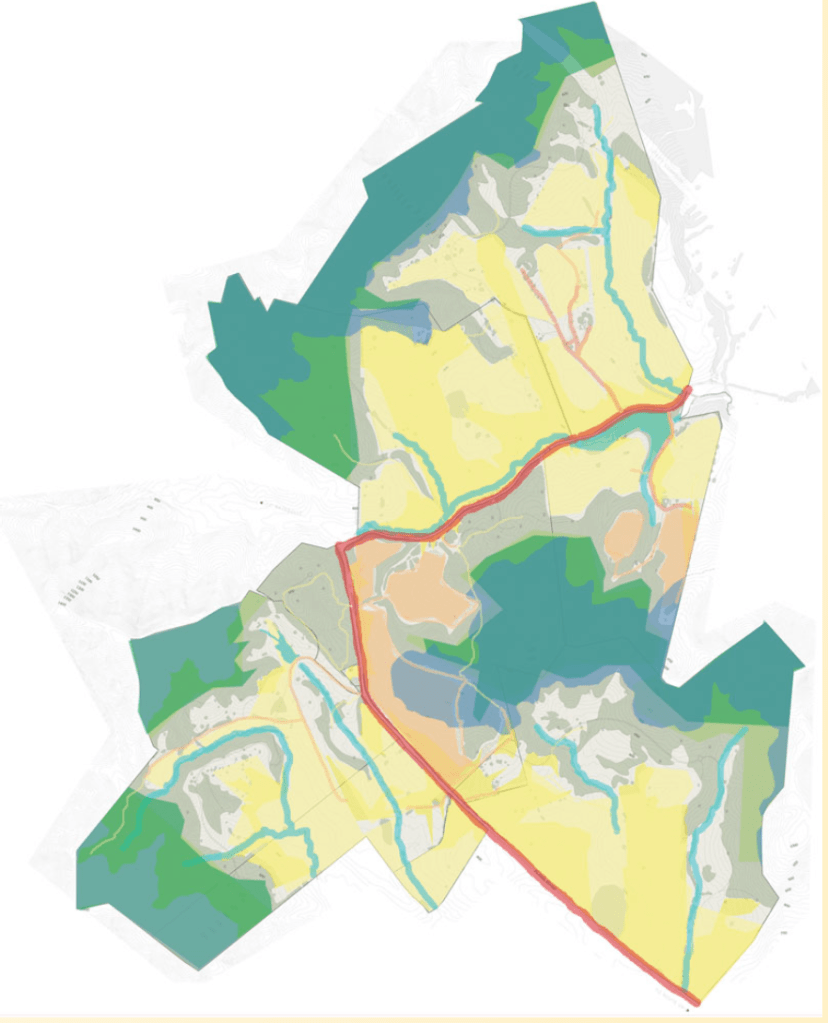

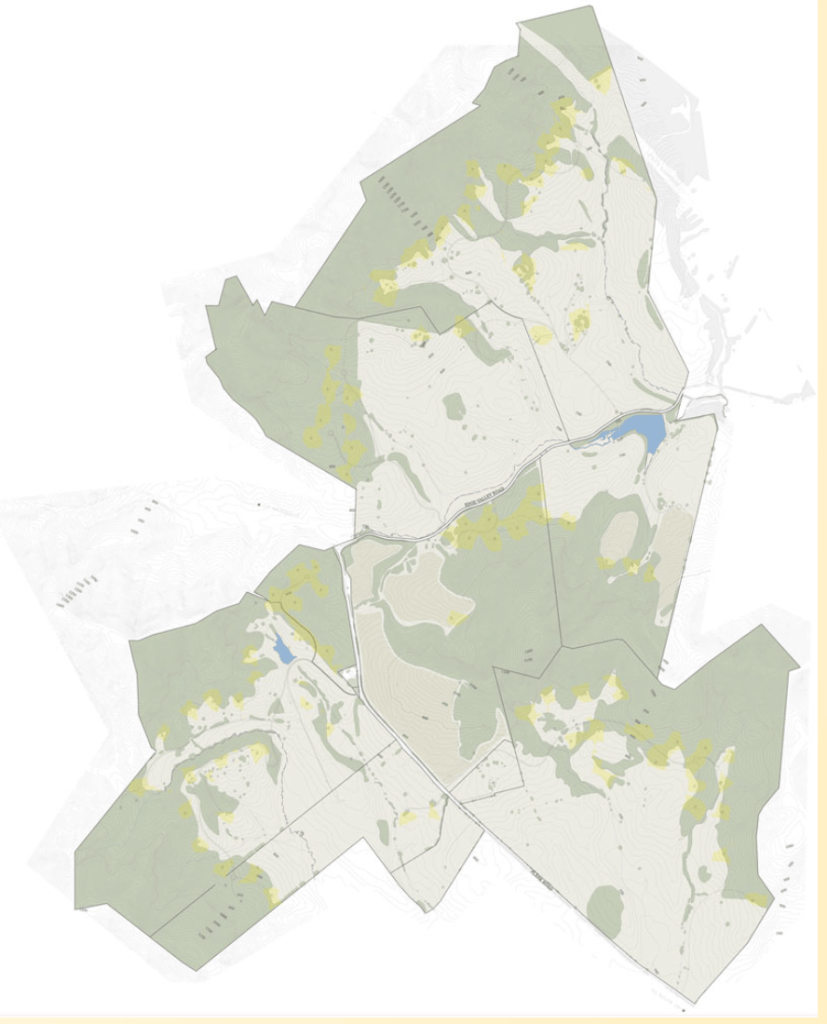

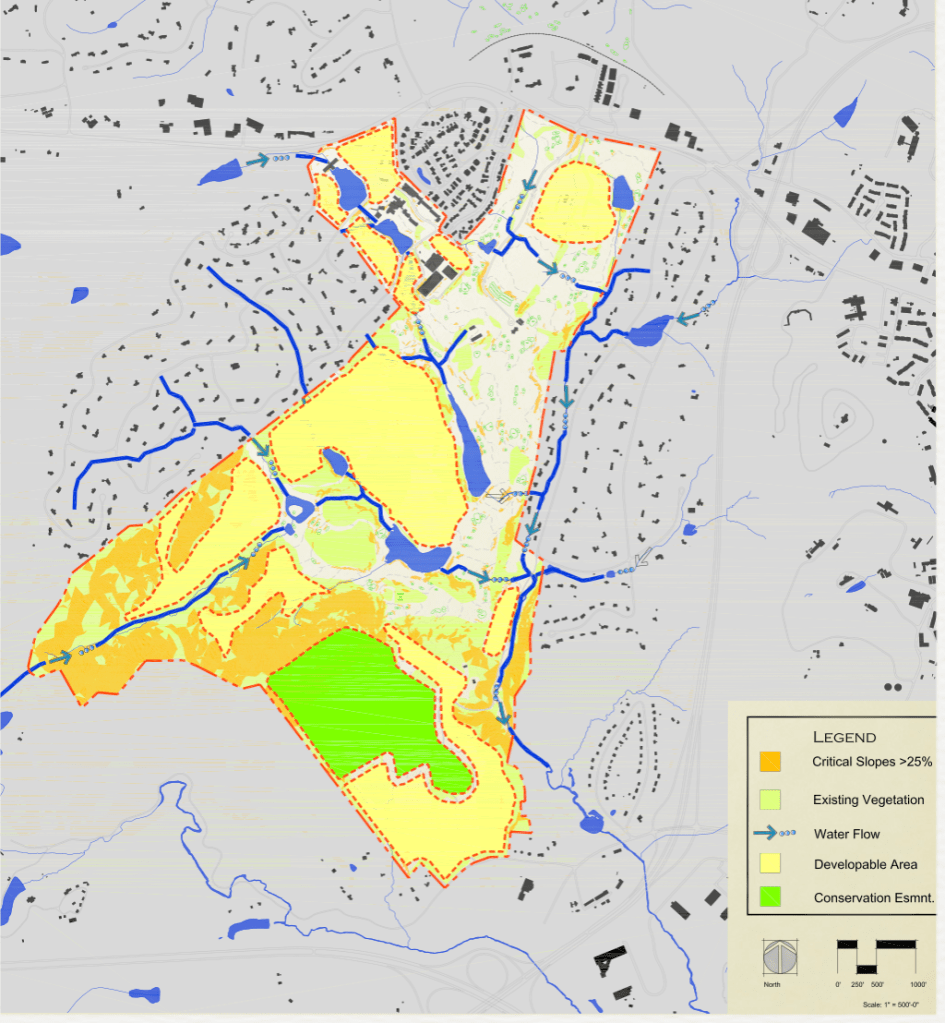

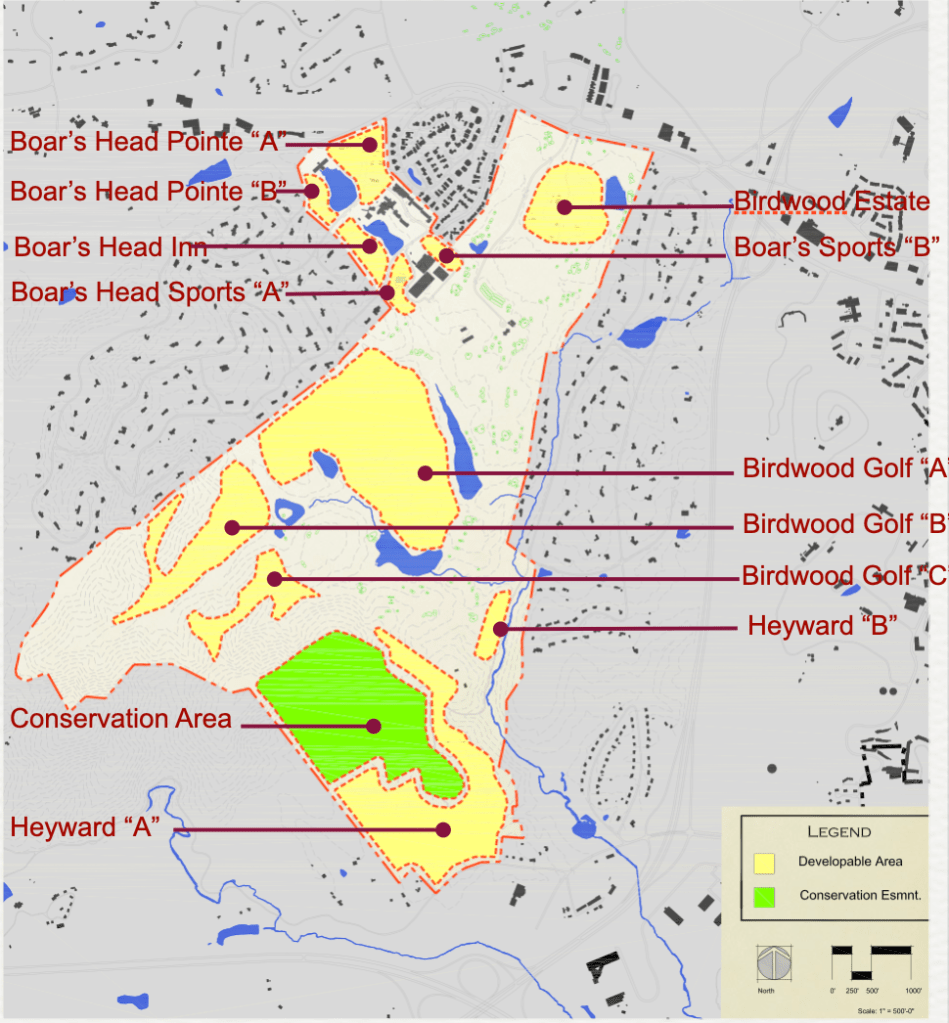

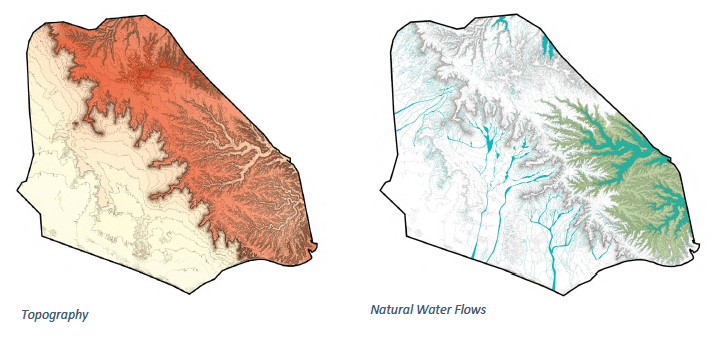

The Site Context follows. The Site Context information is where you lay out what the team is starting with. Begin with the site basics: location, size, general zoning, and current use. Then, move into more specific and practical information. Topography, access points, natural features, adjacent land uses, and existing infrastructure all belong here. Identify key constraints, such as flood zones, wetlands, steep slopes, or easements that may impact the project. Also include the known opportunities, such as road frontage, scenic views, utility connections, or proximity to amenities.

If certain studies, such as geotechnical reports or environmental assessments, have been completed and are available, please note their findings briefly. The point here is not to dump data but to surface what’s important for early design decisions.

Key elements to cover in the Site Context section include:

- Basic site data: size, zoning, location, existing use

- Natural and built features: topography, hydrology, infrastructure

- Environmental and regulatory constraints

- Opportunities and assets: views, access, visibility, adjacencies

- Summary of findings from prior studies or reports

- Known obligations or constraints (e.g., easements, setbacks, community expectations)

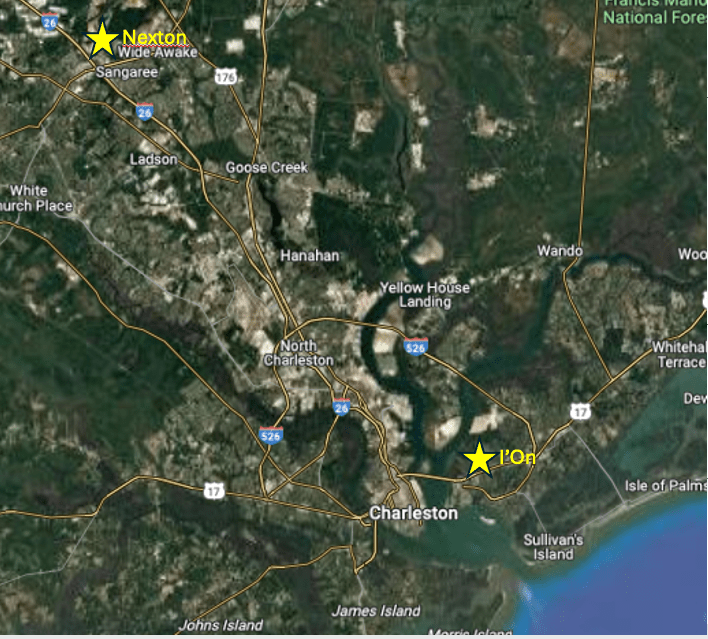

Qiddiya’s natural setting made this part of the brief especially critical. Located on the Tuwaiq Escarpment just outside Riyadh, the site is defined by extremes of elevation, scale, and raw, dramatic beauty. Standing at the edge of a 200-meter-high escarpment, you can stand for miles, down into canyons and across rocky plateaus. The terrain is carved with deep wadis and jagged cliffs. It’s both beautiful and unforgiving, and it shaped everything from circulation and program placement to engineering, grading, and environmental mitigation.

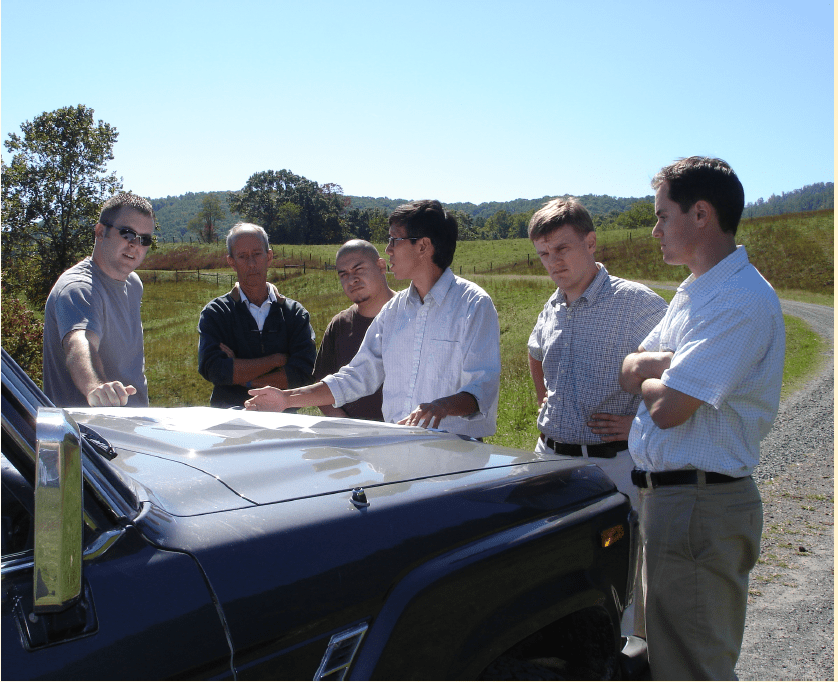

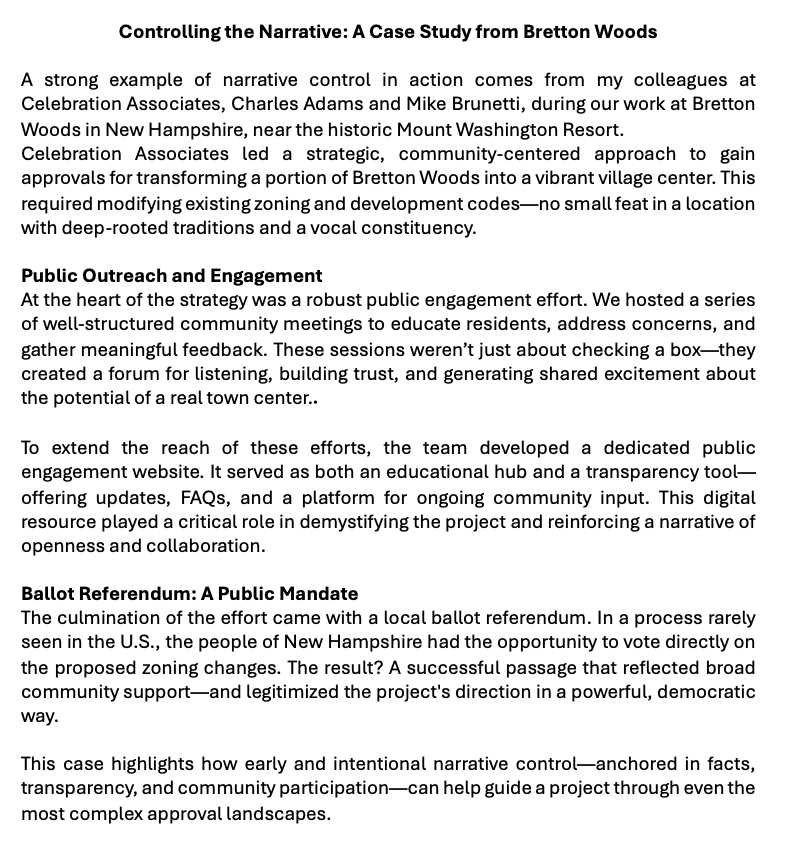

The distinctive challenges and opportunities of the site are why we prioritized helping design consultants understand the terrain from day one. Before pen hit paper, we grounded teams in the physical reality of the site using a suite of materials:

- High-resolution topographic and geological maps

- Drone footage and panoramic imagery

- Environmental overlays and protected zone data

- Climate and solar studies

- Regional context and access mapping

We paired this technical information with experiential narratives: how the light changed throughout the day, how the sound of the wind shifted between the upper and lower plateaus, and what it felt like to descend into the escarpment’s folds. We wanted teams to feel the land. Not just analyze it. Because when they did, their concepts became more authentic and more rooted.

Qiddiya wasn’t a place for off-the-shelf solutions. It demanded an approach that respected the landscape and listened to what it had to offer. That mindset is shaping everything from the placement of buildings to the alignments of access roads.

Qiddiya Stadium Program Highlights

In addition to describing the overall context for Qiddiya, we needed to provide an understanding of how a specific iconic asset is contributing, not only within Qiddiya’s master plan but also in support of the larger Vision 2030 initiative. The Qiddiya Stadium was one of those key assets.

As a cornerstone project within the Qiddiya Sports portfolio, the stadium will anchor a broader network of venues promoting athletic participation, professional development, and lifestyle wellness. It wasn’t just about hosting events. It was about helping to transform sports into a cultural and economic force within the Kingdom—one that inspires health, confidence, and opportunity.

The design brief positioned the stadium as a primary venue for football (soccer) and events. It needed to reflect Saudi Arabia’s aspirations to compete at a global level, with top-tier facilities and an architectural presence that could stand among the world’s best. But it also had to function day-to-day, supporting flexible use, integrating into the broader district, and delivering value beyond game days.

Highlights of the stadium program included:

- Seating for 20,000 spectators, including general admission, premium, VIP, and VVIP zones

- FIFA-standard artificial turf pitch and international-quality support facilities

- Adaptability for non-football events and multi-use activation

- Modern, well-equipped player, media, and operations areas

- Integration with adjacent venues and community-facing uses within the larger sports precinct

The vision for the Qiddiya Stadium was ambitious but grounded. A venue designed not only to host but to inspire. Not just to perform but to endure.

Why It All Matters

A well-crafted Project Overview and Site Context provide your team with a clear starting point. They orient people. They reduce confusion. And they keep everyone, regardless of their discipline, focused on what matters most. When done right, the Project Overview and Site Context become the quiet foundation of everything that follows.

So, before you move into conceptual or schematic design, take the time to get these two pieces right. Strip out the fluff, organize the facts, and use plain language. Because in complex projects, clarity is one of the most powerful tools you have.