You’re in the room. Slides are on the screen. Coffee’s brewing. Ideas are flowing. The concept is good. The team is strong. Everyone’s excited.

Then you ask one question: “So who signs off at each stage?”

Silence.

Some folks look down. Others look at each other. A few shrug. You just found the gap. And it’s a big one.

It’s not the design.

It’s not the budget.

It’s the process.

Every great project begins with vision. But vision alone doesn’t get buildings permitted. Streets approved. Funds released. Or site work started.

Vision needs a map. A map that covers not just what we’re building, but how we’ll get it approved. A “vision’ with an execution “plan” is just a dream. Likewise an execution plan without a “vision” is a waste of time.

I’ve spent three decades managing the design and development of high-profile projects—from Celebration and I’On in the U.S. to Qiddiya and Trojena in Saudi Arabia. And if there’s one truth I’ve learned, it’s this:

The design process must include a design review and approval strategy from day one.

And that strategy needs to cover both internal and external paths—because delays don’t usually happen when the team’s working. They happen when no one’s sure who needs to review what, when, or how.

Let’s fix that.

Designing the Design Process

During the Strategic Definition stage of a project, teams often focus on establishing the creative brief, aligning business goals, and setting design quality standards. All essential. But often overlooked?

The roadmap for how decisions get made and approvals happen.

Whether it’s your own internal organization or a town planning board halfway across the country, every decision point needs a clear path. Without it, you risk confusion, rework, cost overruns, and endless meetings where nobody quite knows who has the final say.

So where do you begin?

Start with two questions:

- Who are the stakeholders?

- What’s their role in the review process?

(See a recent article on Stakeholder Identification and Engagement)

Internal Review: Who, When, and Why

Inside any organization, there are different levels of review. You’ve got executives, project managers, cost consultants, branding teams, and sometimes joint venture partners—all of whom may have something to say. But not everyone needs to be involved at every step.

Match the profile of the project to the level of internal oversight it requires.

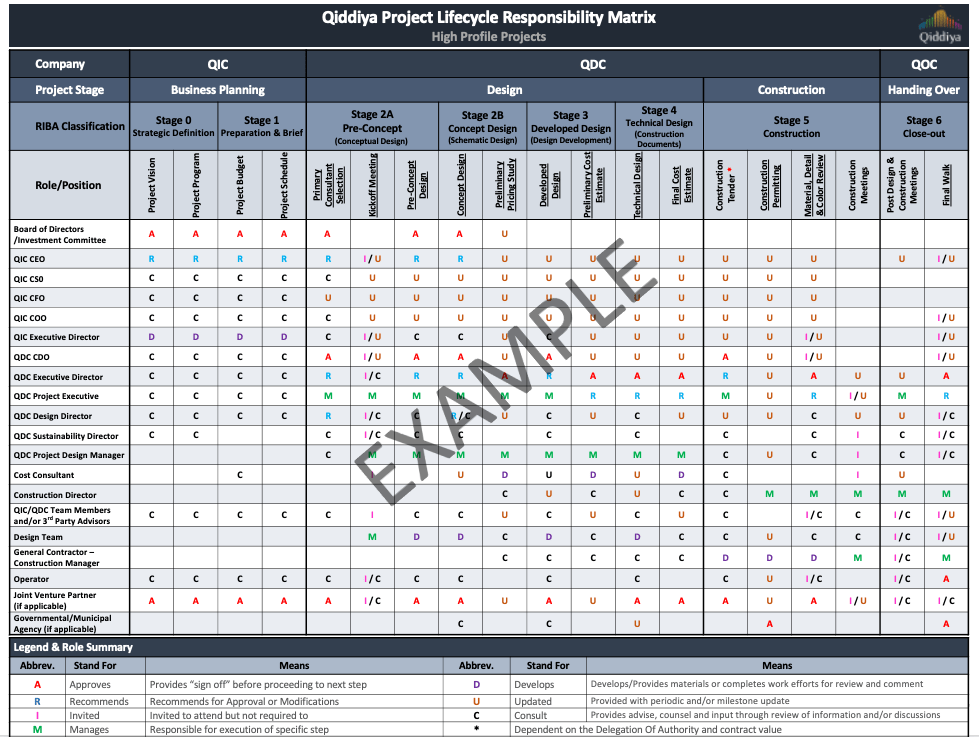

At Qiddiya, where I served as Acting Executive Director for Planning & Design, our projects ranged from cultural flagships like opera houses and mosques to supporting infrastructure. Some were “nation-building”; others were context-driven. We couldn’t afford a one-size-fits-all process.

So we designed our own design review and approval process. Before we even got to schematic design.

Instead of using a traditional RACI (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed) or RAPID (Recommend, Agree, Perform, Input, Decide) matrix, we created something tailored:

ARIMDUC:

- Approves – Signs off before the next step

- Recommends – Suggests for approval or modification

- Invited – Optional attendee with no decision role

- Manages – Leads the step or task

- Develops – Produces the materials to be reviewed

- Updated – Kept informed at key milestones

- Consulted – Provides expertise or review comments

Not pretty. But it worked.

Every team member knew their lane. Every asset had a review path. And it scaled depending on the project profile.

We developed an internal matrix that paired asset classes—Iconic, Signature, Class A through D—with the ARIMDUC roles. For example, an Iconic asset like a national sports stadium might require final approval by the Board of Directors, recommendation by the Executive Committee, and input from the Design Advisory Panel. Meanwhile, a Class C office building might require only departmental sign-off and functional input from cost consultants.

This matrix helped establish clarity across dozens of project types. It also supported speed, especially when approvals were needed quickly but without sacrificing quality or governance.

One of the most important features? We made the ARIMDUC matrix a shared resource—not just a behind-the-scenes tracking tool. It lived on our internal collaboration platform, embedded into dashboards used by all teams. No matter your role—planner, architect, or executive—you could see who was doing what, when decisions were needed, and what form of input was required.

In short, we didn’t just manage the design. We managed the design process infrastructure.

If you’re leading a complex organization or managing multiple projects in parallel, creating this kind of system can make or break your ability to deliver. It’s less about bureaucracy and more about giving your team a roadmap and a rhythm.

External Review: Why Local Always Wins

You might be building a world-class destination. You might have starchitects on board and globally admired master planners. But none of that will move your plans through the local approvals process unless you understand one fundamental truth:

Design may be global, but approval is always local.

This is where good projects stall. And where great ones sometimes die.

I’ve worked on projects in over a dozen municipalities. Each one is different. Different processes. Different politics. Different definitions of success.

Take Mount Pleasant, SC versus Berkeley County, SC. Both in the same region. Entirely different approval processes.

Mount Pleasant vs. Berkeley County: A Tale of Two Approvals

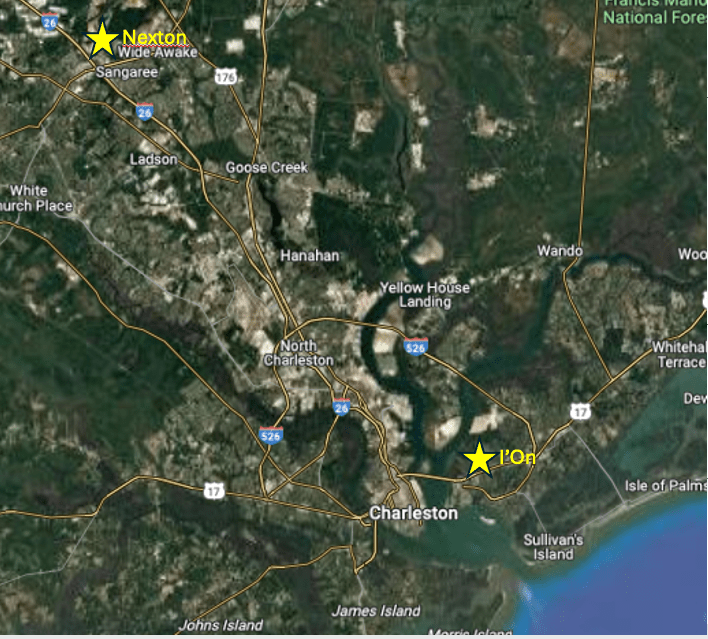

Let’s look at two real-world examples. Both are in South Carolina. Both were large-scale, mixed-use, master-planned communities. One faced enormous community initial pushback prior to becoming recognized as one of the premier examples of New Urbanism development. The other quietly became a regional success story.

What made the difference?

Let’s compare the approval journey for:

- I’On in Mount Pleasant

- Nexton in Berkeley County

Context and First Impressions

I’On was an infill traditional neighborhood on about 243 acres. It was ambitious—compact, walkable, mixed-use, and patterned after historic Charleston. And it landed right in the middle of a fast-growing town already wrestling with change. That meant intense public scrutiny from day one.

Nexton, by contrast, was a 5,000-acre greenfield development launched by a timber company turned developer. It had the backing of regional planners and was positioned in an area targeted for growth. Public opposition? Minimal. The focus was infrastructure.

The Review Paths Compared

Mount Pleasant

- Requires pre-submittal staff meetings

- Mandates an Impact Assessment for projects triggering thresholds (e.g., 75+ peak hour trips)

- Uses a Planning Commission for recommendation

- Final decision lies with Town Council

- Public hearings are highly attended

- Design Review Board involvement for commercial architecture

- Subdivision and infrastructure approvals handled in separate steps by the Town’s staff

- Known for strong citizen involvement, vocal neighborhood associations, and sometimes unpredictable politics

Berkeley County

- Fewer layers at the start

- Allows for a Planned Development Mixed Use (PDMU) zoning

- Negotiates Development Agreements that lock in rights and obligations for 10–20 years

- Focuses more on traffic and school impacts than architectural detailing

- Less public hearing conflict for greenfield areas

- Uses a moratorium and mitigation checklist for newer projects to address infrastructure proactively

- Projects are often phased under a long-term agreement, giving more certainty to developers

What This Means in Practice

Mount Pleasant requires you to win not just on planning merit—but on community and political grounds. I’On had to revise its plan multiple times. It removed apartments, scaled down commercial areas, and reduced unit counts—all in response to neighbor concerns and Council votes.

Berkeley County emphasizes up-front infrastructure planning. If you can show that you’re solving traffic, funding schools, and providing long-term value, you’re on solid ground. Nexton’s developers coordinated the timing of a major highway interchange with the county, DOT, and even the Ports Authority. That infrastructure investment was the ticket to long-term approval and phasing.

In short:

- In Mount Pleasant, public sentiment was the wildcard.

- In Berkeley County, infrastructure was the bar.

How to Plan for Local Review from Day One

You can’t fast-forward through the public process. But you can do a lot to make sure it doesn’t derail your timeline—or your vision.

Here’s where strategy turns into real-world execution.

During the Strategic Definition phase, most teams are heads-down crafting the design brief, aligning business goals, and sketching out early concepts. That’s good. But there’s a second track that needs just as much attention: your external approval strategy.

This means planning the process of getting to yes just as carefully as you plan the project itself.

Start by mapping your approval terrain. That means understanding not just the basic steps—like rezoning or site plan approval—but who is involved, what concerns they’re likely to raise, and how those issues tend to play out in your jurisdiction.

If it’s a place like Mount Pleasant? Plan on multiple rounds of public input and anticipate highly organized citizen groups. You’ll need a communications plan just as much as a design strategy.

If it’s more like Berkeley County? You better have your traffic mitigation plan airtight—and your development agreement in place before the first shovel hits dirt.

Next: Engage early.

A surprising number of developers skip this step or treat it as a formality. It’s not.

Pre-application meetings with planning staff aren’t just about checking boxes. They’re your opportunity to build relationships and learn how the local process really works.

And if the stakes are high, talk to councilmembers early too, especially if they have the final say on approvals. Understand what matters to them. Is it school crowding? Neighborhood compatibility? Fiscal return? It would be disastrous to have all the community meetings, get planning commission’s approval only to find out a council person or two has unknown or unaddressed buttons that will cause them to disapprove your project.

Don’t pitch your project yet. Just listen. Take notes. Then go back and shape your strategy with those realities in mind.

Third: Tailor your technical studies.

Don’t wait for planning staff to ask for a traffic study or a stormwater plan. Come prepared with real data. And not just to meet the minimum requirements—use it to tell your story.

If your plan generates 800 vehicle trips at peak hour, explain how you’ll mitigate that. Not with vague promises—show the turn lanes, the signal timing, the funding sources. Show that you’ve already met with DOT and gotten alignment.

Do the same with schools, fire service, water and sewer. If you can show that you’ve thought through the impacts and have a plan to handle them, you’ll build trust with reviewers and decision-makers.

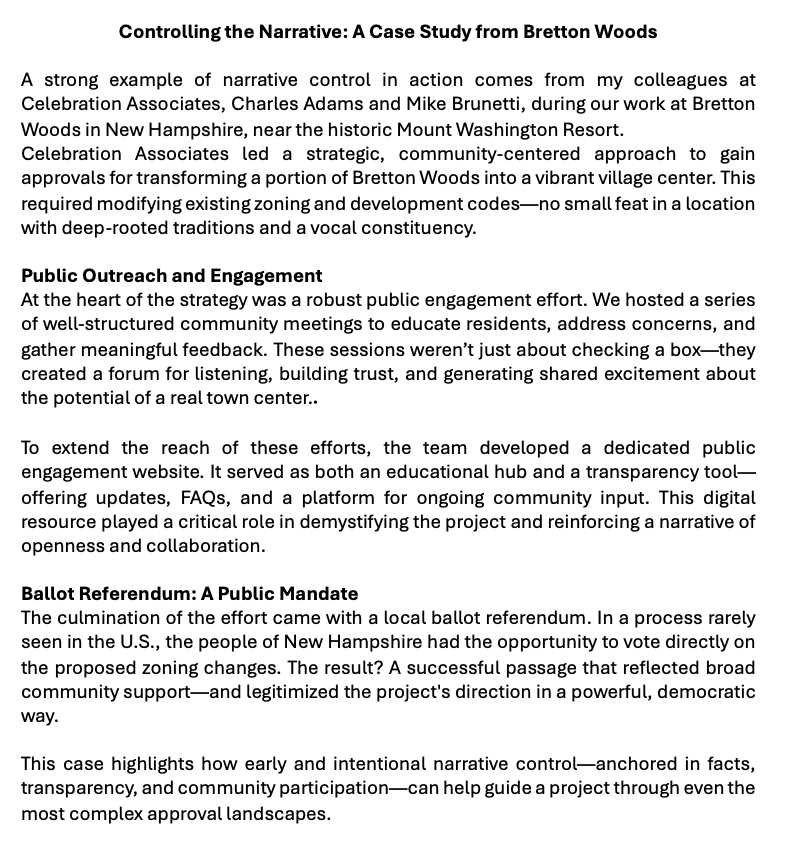

Fourth: Control your narrative.

This is where many teams fall short.

You need a clear, compelling way to explain your project—not just to planners, but to residents who may never have heard terms like “PUD” or “TND.” Show what’s in it for them. Parks. Trails. Local shops. Tax revenue. Road improvements.

And don’t rely on public hearings to do this. Host your own community meetings. Launch a simple website. Offer one-page summaries and FAQs. These things matter—because public perception can be shaped long before your hearing is scheduled.

Finally: Anticipate iteration.

The perfect project doesn’t exist. And the first version of your plan probably isn’t the one that gets approved. That’s not a failure—it’s the nature of local development.

What matters is how you adapt.

Build in time to respond to staff comments. Have a Plan B ready if a particular road connection or building type triggers opposition. Know your red lines—and your flex zones.

Approach the process with humility, but don’t lose your strategic edge. You’re not just seeking approval. You’re building trust.

What To Do Next

If you’re leading a real estate development project—whether it’s a walkable neighborhood in the Southeast or a destination mega-project in the Middle East—internal clarity and external readiness are your twin engines.

So here’s where to start:

- Document your internal design approval path. If it’s fuzzy, make it visible. Define who approves, who recommends, and who simply needs to be kept in the loop. (Consider ARIMDUC if RACI or RAPID isn’t cutting it.)

- Identify every external stakeholder you’ll need to work with. Agencies, utilities, public boards, neighborhood groups, political bodies. Know their review process and what they care about.

- Build your process map. Don’t wait until schematic design to figure out how you’ll get zoning, infrastructure, and site plan approvals. Lay out the sequence now.

- Engage early. Communicate clearly. Adjust when needed.

Design may start with vision. But development moves with process.

And the best teams? They design both.

Leave a comment