She sat across the table, legal pad in hand, confident in the potential of her family’s land.

Three hundred and fifty acres of rolling hills and forest just outside a growing town—she believed it was all developable. Maybe not immediately, but soon. The plan was to subdivide and sell, maybe even build a family legacy project. The numbers looked good. On paper, it was enough land to change her family’s financial trajectory for generations.

But within an hour, that hope had shifted.

Once she started to learn about the impacts brutal, but essential facts, such w slope analysis, wetlands delineation, utility easements, and road access, the reality came into focus. Of the 350 acres, maybe 110 had meaningful development potential. The rest? Too steep, too wet, too restricted, or simply unreachable without major investment.

It wasn’t a dead end—but it was a reset.

I’ve had numerous encounters like the hypothetical one described above which unveiled and reinforced a truth that too many people skip past in their initial excitement: not all land is buildable, and not all constraints are obvious.

In real estate and community development, your design efforts are only as good as the ground they stand on. And that’s why due diligence in the Strategic Definition stage isn’t just useful—it’s essential.

Bundoran Farm: Preservation Development Grounded in Due Diligence

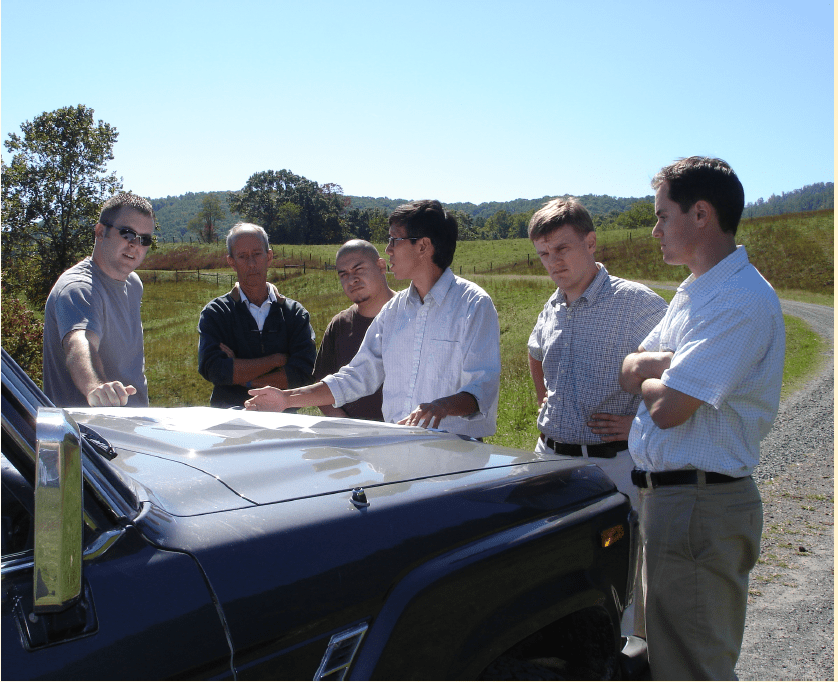

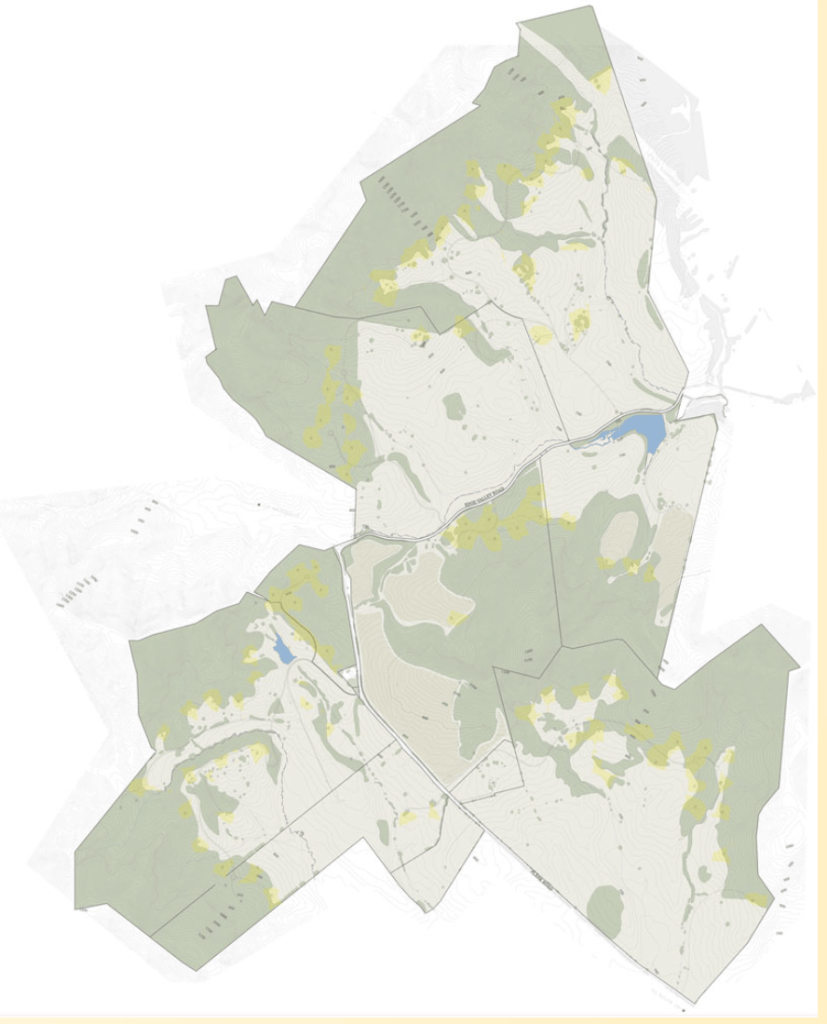

When our team—led by QROE Preservation Development and Celebration Associates—first set foot on Bundoran Farm, a 2,300-acre property just outside Charlottesville, Virginia, we didn’t begin with a concept plan or a glossy vision statement.

We began by walking the land.

Every ridge. Every fencerow. Every stretch of woods, pasture, and creek.

We walked it with purpose—and with humility.

At the helm of that exploration was David Hamilton of QROE, joined by a multidisciplinary team that would eventually include Audubon International, McKee Carson, Roudabush Gale, and Biohabitats. And crucially, we had the benefit of Eddie Mawyer, Bundoran’s longtime farm manager—born and raised on the property—who knew the land more intimately than any GIS layer ever could. He was our compass, often pointing out potential red flags and opportunities that wouldn’t appear on any map but mattered deeply on the ground.

That ethos—boots on the ground before pencil on paper—set the tone for everything that followed.

A Landscape Worth Protecting, and a Pattern Worth Reimagining

At the time, we were confronting more than just a blank piece of land. We were responding to a broader crisis in how we as a society were developing our agrarian landscapes—unsustainably, inefficiently, and destructively.

Across the country, rural land was being carved into cookie-cutter subdivisions.

Productive farmland was vanishing.

Viewsheds were scarred.

Wildlife corridors were severed.

Watersheds degraded.

And worse still, the process pitted farmers and landowners against environmentalists and planners, each side forced into an adversarial stance by a system that lacked nuance or imagination.

Even traditional conservation tools had unintended consequences. Easements often reduced land value, segregated uses rigidly, or locked landowners out of financially viable paths forward. These approaches saved scenery, but not always place.

We believed a better path existed—one that could:

- Allow a farmer to sell at fair market value

- Protect productive agricultural land

- Preserve the rural character and working landscape

- Encourage ongoing stewardship

- Permit compatible residential use

- Attract buyers seeking authentic countryside living

- Minimize long-term fiscal burden to the county

That model became what we now call Preservation Development.

Preservation Development at Bundoran Farm was not a workaround—it was a comprehensive approach to design and development that accounted for:

- Residential land value and generational wealth transfer

- The continued stewardship of farmland and forest

- Environmental resilience and ecological protection

- Integration—not segregation—of land uses

- Design grounded in traditional rural settlement patterns

- Community and fiscal sustainability

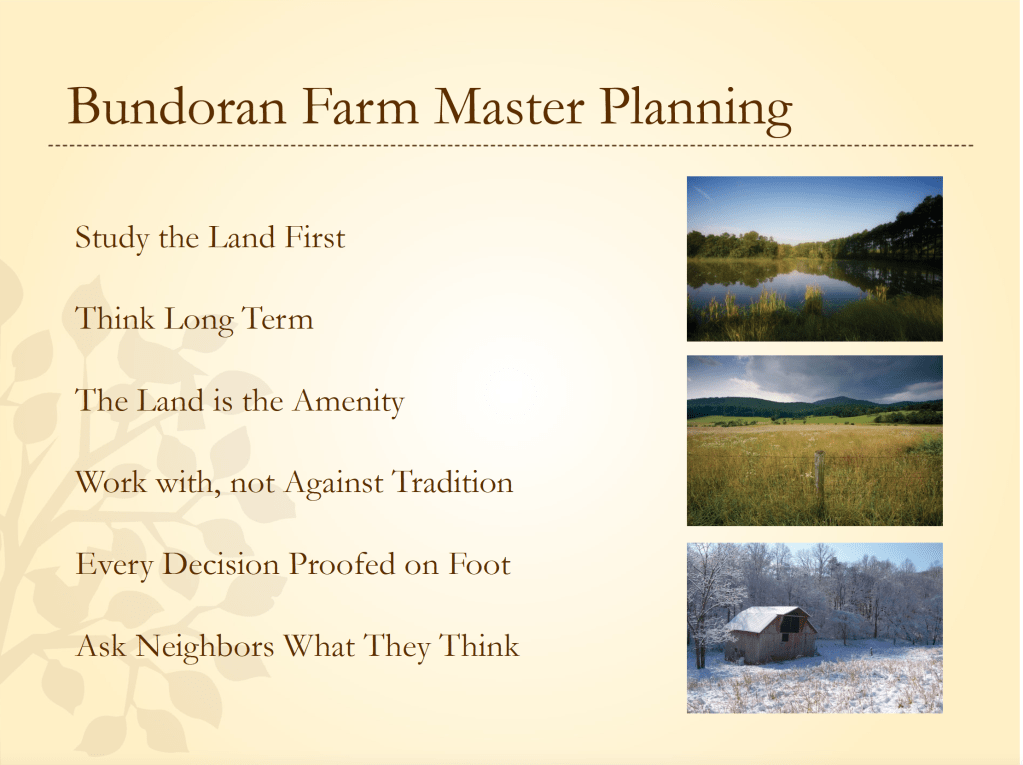

We established a framework of six guiding principles:

And then we got to work—carefully mapping everything that mattered.

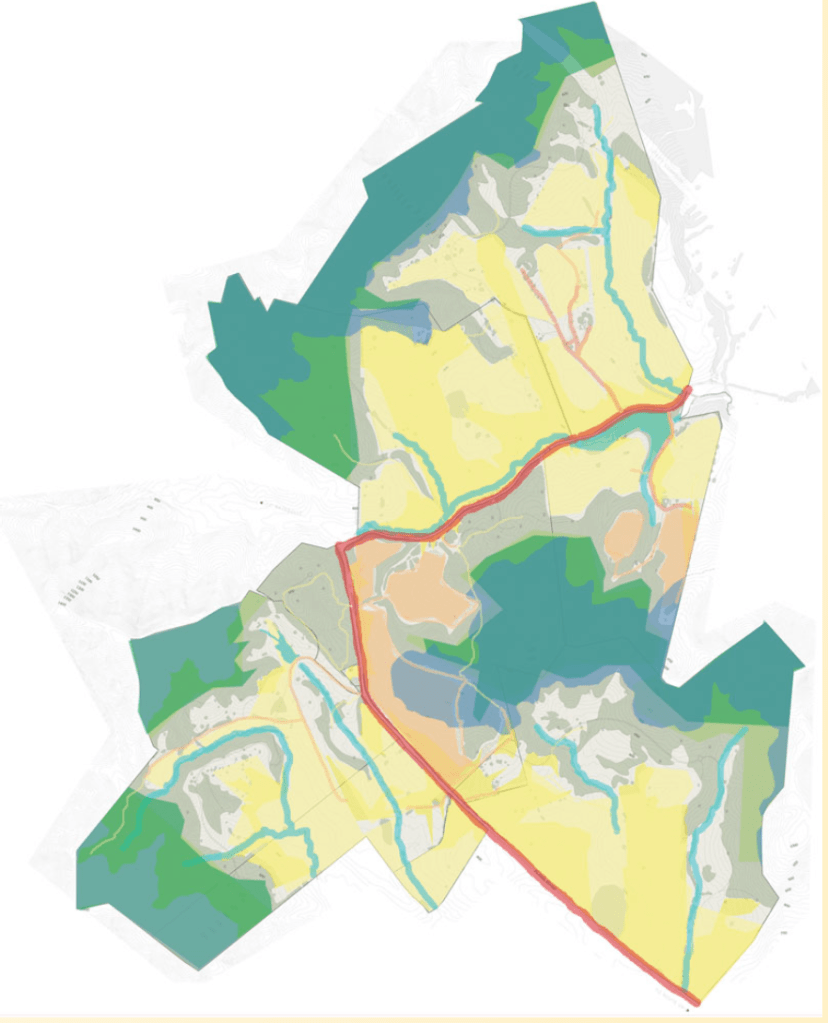

Mapping What Others Might Miss

We studied:

- Existing farm operations

- Natural features—streams, wetlands, woodlands, wildlife habitat

- Topography, soils, and drainage patterns

- Old farm roads, trails, even cattle paths

- View corridors from public roads and neighboring properties

- Productive pasture and orchard soils

- Cultural assets and historic homesteads

This was true site analysis—both qualitative and quantitative, informed by local knowledge, ecological science, and traditional land use wisdom.

Design That Emerged from the Landscape

Rather than dividing the land equally or placing homes in “optimal market positions,” we fit them into the seams—the edge spaces between forest and field, on gentle slopes, in locations that would not disrupt farming, views, or wildlife patterns.

Each homesite was intentionally modest—development envelopes of approximately 0.75 acres were set within much larger lots, many of them ranging from 21 to over 100 acres.

In the end, we located 108 homesites—a 30% reduction from the 155 allowed under Albemarle County’s zoning.

We also ensured that more than 90% of the land remained permanently protected.

A Place, Not Just a Project

Buyers weren’t just purchasing homes—they were becoming part of a working, evolving landscape with a clear identity and long-term vision.

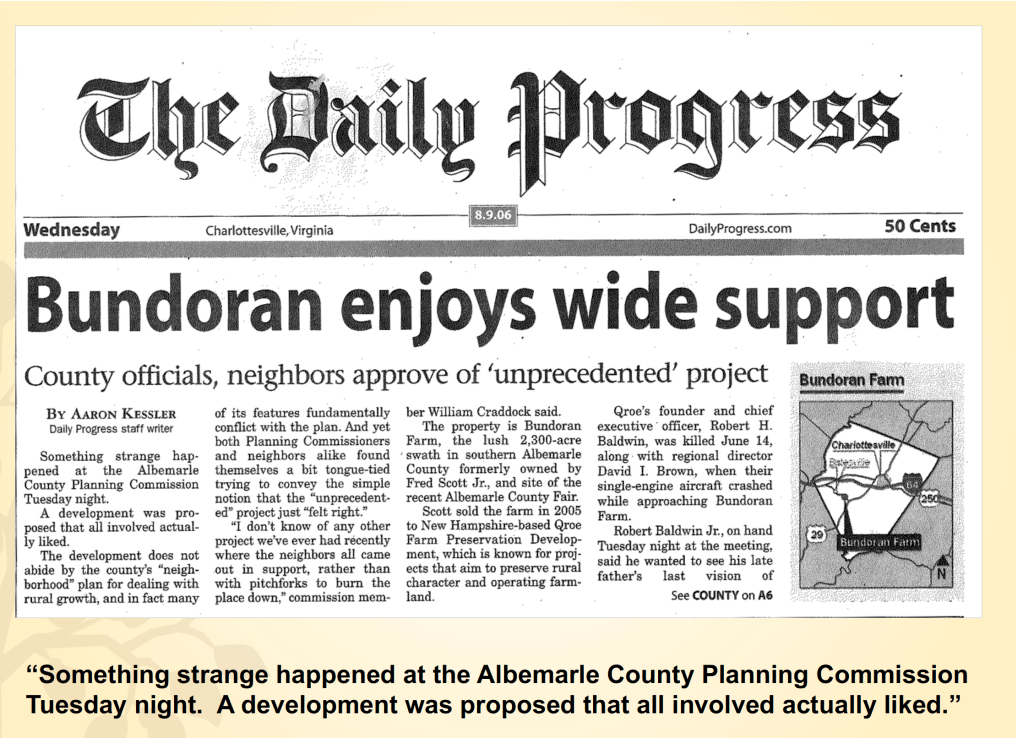

Local stakeholders didn’t fight the plan—they supported it.

Albemarle County didn’t have to be convinced—they approved it unanimously.

Bundoran Farm stands as proof that rigorous site due diligence, coupled with visionary yet grounded development thinking, can produce places that are as financially viable as they are ecologically and culturally respectful.

The land had a story to tell.

We just took the time to listen.

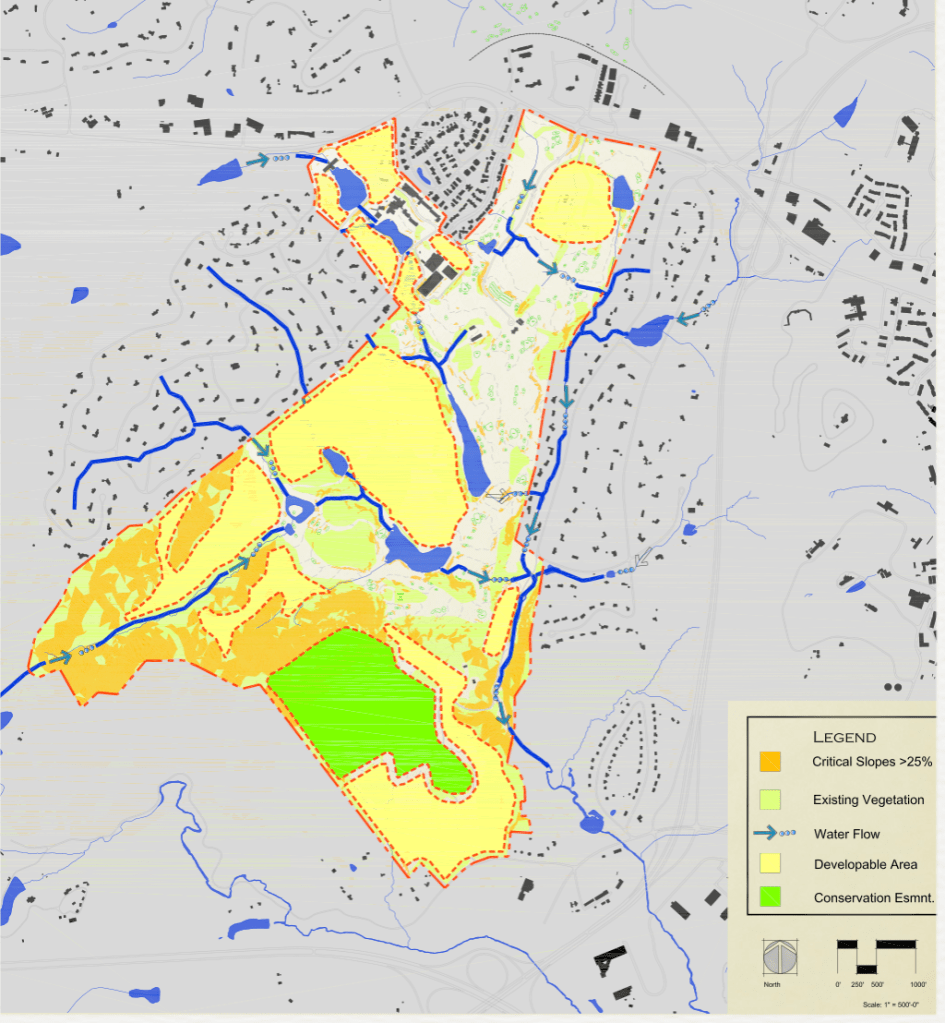

Boar’s Head and Birdwood: Strategic Due Diligence at the Institutional Edge

While Bundoran focused on preservation in a pastoral setting, our work with the University of Virginia Foundation near Boar’s Head Resort and Birdwood Golf Course dealt with complexity at the edge of an urban institution.

Celebration Associates was retained to analyze potential development options for six contiguous but distinct parcels totaling 787 acres. These lands were part of a broader strategy to align with UVA’s institutional mission while honoring the site’s recreational, historic, and environmental context.

The goals were clear:

- Explore and articulate a vision for the property

- Lay the foundation for “why” development should occur

- Determine where development might be appropriate

- Recommend compatible land uses

- Define actionable next steps

To ground the vision, a Clarity Session led by Vancouver-based Envisioning + Storytelling helped surface strategic aspirations from Foundation leadership. These emergent findings created a strong foundation for place-based decision-making.

From there, we turned to Land Resource Mapping and Analysis, drawing from previous studies commissioned by the UVA Foundation and Albemarle County and the City of Charlottesville’s GIS data. Our analysis began broadly and zoomed into site-specific assessments.

Context and Constraints

We reviewed:

- Zoning (ranging from Highway Commercial to R-1 Residential)

- Existing land uses: hospitality, sports, institutional, and limited retail

- Historic designations (Birdwood Estate is listed on the National Register of Historic Places)

- Topography (from gentle slopes to steep, separated terrain)

- Hydrology (multiple streams, creeks, and small ponds)

- Vegetation (perimeter buffers and modest interior coverage)

- Site access, circulation networks and traffic capacity and impacts

- Utilities (water, sewer, electrical, teledata) both existing and proposed to understand locations and capacity

After applying constraints such as conservation easements, critical slopes, flood areas, and already developed land, we identified just 213 net developable acres—scattered in distinct development “islands.”

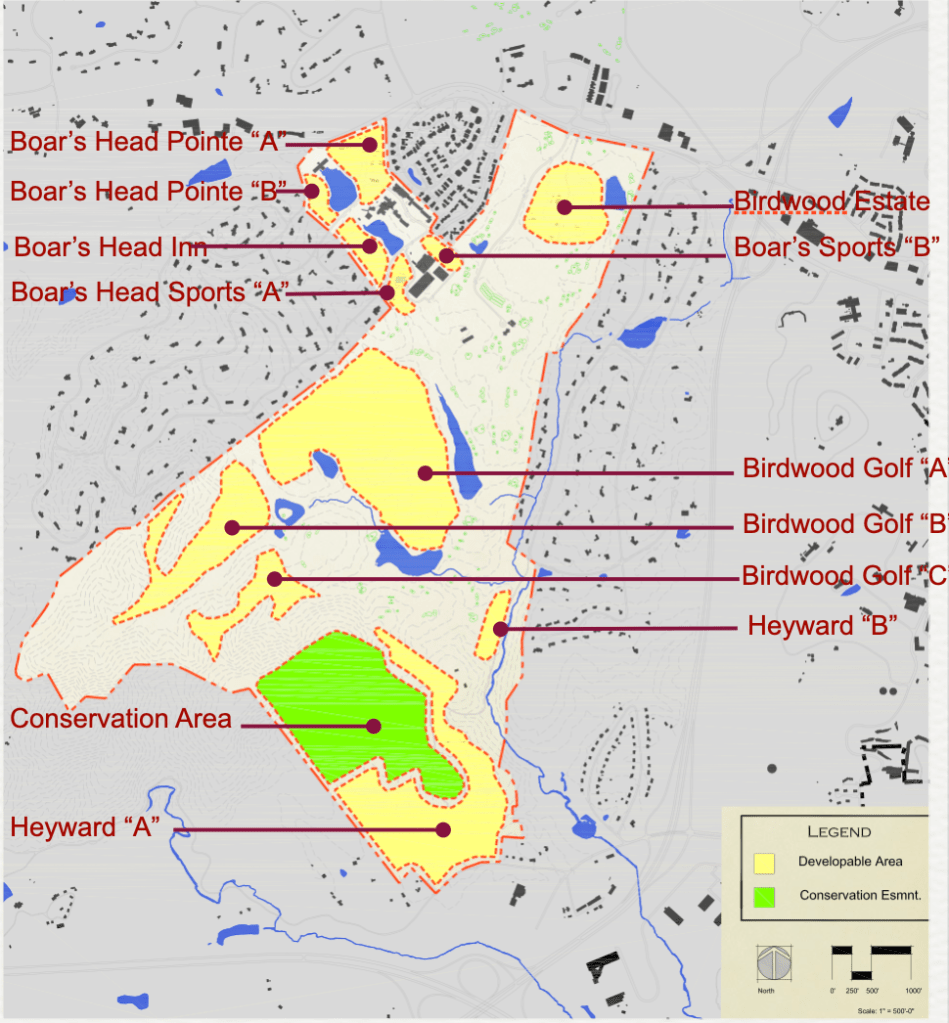

Strategy by Parcel

Each parcel was then studied individually:

- Evaluating adjacent uses

- Recommending probable land uses (residential, wellness, institutional, or hospitality-related)

- Estimating development yields

- Offering design guidance (e.g., viewshed protection, trail connectivity, strategic access points)

This process produced not a master plan, but a framework for action. It gave the UVA Foundation clarity about what was possible, what was wise, and how to proceed in a way that minimized risk and aligned with mission.

In the end, Boar’s Head, like Bundoran, reminded us that meaningful development starts not with ambition, but with awareness.

It begins with listening—to the land, the context, the community, and the story waiting to unfold.

So… What’s Your Land Telling You?

If you’re working on a new project—whether it’s five acres or five hundred—pause and ask: have you really let the land speak yet?

Have you walked it with intent? Talked to the neighbors? Cross-checked the zoning with the soil tests? Thought through the market dynamics?

Have you asked, not just “what do we want to build?” but “what should be built here, now, in this context?”

Due diligence isn’t paperwork. It’s insight. It’s the foundation of every wise design decision that follows.

If you get it right, the rest of the process becomes smoother, more aligned, and more impactful.

Let’s make sure your next great idea is rooted in a deep understanding of the land it hopes to shape.

Let the Land (and the Context) Lead

If you’re working on a new project—whether it’s five acres or five hundred—pause and ask: have you really let the land speak yet? Site due diligence is what grounds vision in reality. It does more than de-risk—it reveals possibilities you can’t see on a site plan alone.

It answers questions like:

- Can this parcel be accessed safely and affordably?

- Is this soil buildable or prone to expansion?

- Will the community fight this proposal—or embrace it?

- How does our idea align with market demand, infrastructure capacity, and environmental stewardship?

- Are there or will there be appropriate levels of service by utilities

Every project I’ve worked on that succeeded—truly succeeded—started with this kind of discipline.

And it wasn’t a chore. It was a creative process. A way to discover the project hidden within the site’s limits and potentials.

Leave a comment