You’ve wrapped up the Strategic Definition stage. You’ve answered the big questions—Why, How, Who, What, Where, and How Much. The vision is clear. The team is aligned. The early financial modeling looks solid.

Now comes the next question:

What exactly are we designing?

That’s where the Design Brief comes in.

If you’ve followed my past posts on The Barnes Perspective, you already know how often I come back to this. Strategic Definition is one of the most overlooked—and misunderstood—parts of the development process. A strong vision and a high-level plan aren’t enough. Neither is a financial model or a site strategy.

You still need a document that bridges the gap between intention and implementation.

That’s the role of the design brief.

When done right, it becomes the single source of truth for your architects, planners, engineers, developers, and investors. It doesn’t just describe the project; it also highlights its significance. It directs it.

Let me show you how.

What Is a Design Brief?

A Design Brief, sometimes called a project brief or architectural program, is the foundational document that guides the entire design process. It turns a project’s vision and intent into something actionable. For architects, planners, engineers, and stakeholders, it serves as a working reference that shapes decisions from early concepts to final delivery.

In real estate and community development, a well-crafted brief is essential. It defines scope, goals, and constraints before design begins, when decisions are still cheap to change. Without it, teams can lose clarity, get misaligned, or waste time solving the wrong problems.

The Design Brief matters even more in complex projects, such as mixed-use communities or vertical, multi-program buildings. These projects require a framework that integrates various uses, including residential, commercial, civic, and recreational, into a coherent whole. A good design brief creates that framework. It brings order to complexity by breaking the project into parts, assigning priorities, and flagging constraints that shape the design.

The strongest briefs share three traits. They’re clear and free of jargon or fluff. They’re comprehensive, covering everything from the big picture to the specifics that matter. They’re contextual and tailored to the project’s location, audience, and stage of development.

A design brief is not a pitch deck. It’s not a feasibility study or a glossy PDF built for marketing. It’s a tool for real decision-making. It should provide your team with what they need to move forward confidently and stay aligned, not just in concept but in detail.

When done right, it provides a snapshot of the site and surrounding context. It outlines a breakdown of the program, maps performance criteria, and documents stakeholder input. All of this gives shape to the project while leaving room for creativity and technical judgment as design work progresses.

That’s the role of the brief. It doesn’t aim to answer every question. It aims to ensure everyone is asking the right ones.

Avoiding the Trap of Premature Precision

At NEOM, we used the term “Initial Asset Brief” for what many would call a Design Brief. The format originated from Aramco, the world’s largest oil producer, and was initially developed for industrial assets, such as refineries and pump stations. Given the heavy engineering focus of those projects, it made sense to include extensive technical data right from the start.

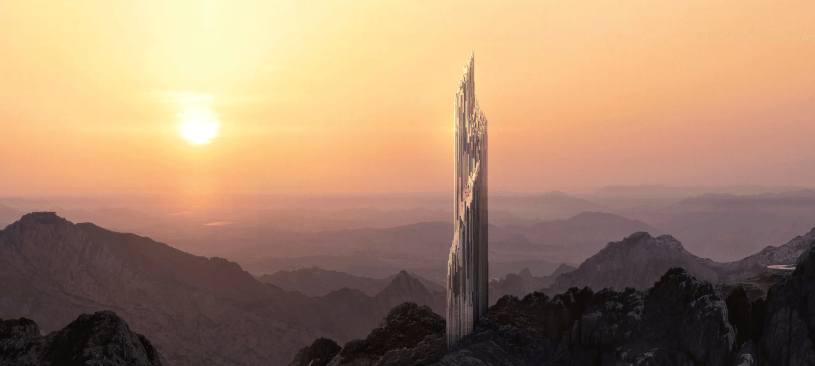

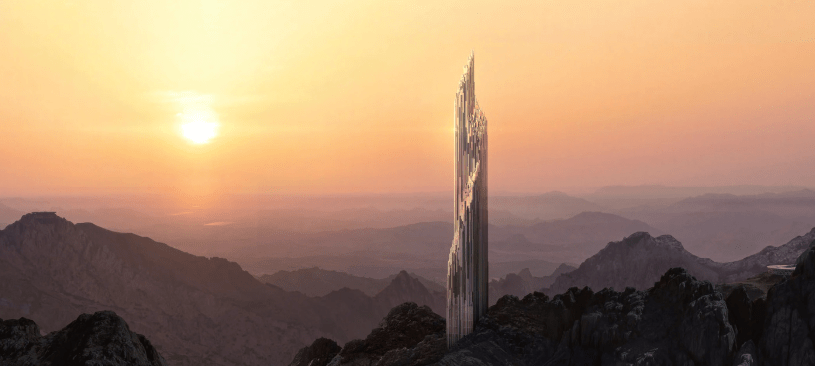

But that approach didn’t translate well to what we were designing at Trojena, where we had a 330-meter-tall tower perched on one of the tallest peaks of the site or a ski village that contained. 2 hotels, numerous apartments, a village center, and ski slopes on top of and integrated throughout the building.

Early versions of the brief requested everything from electrical load estimates to single-line diagrams. This request came before a schematic design even existed. The intention was good: promote engineering readiness. But the result was confusion, higher costs, and misaligned priorities.

If you’re being asked for wastewater outputs before the building’s use is even defined, you’re not planning. You’re guessing in excessive detail.

The name said it all: Initial Asset Brief. We often had to remind teams what “initial” and “brief” are supposed to mean. Early-stage documents should point the way forward, not pretend to have answers that aren’t yet knowable.

While working with NEOM’s Engineering and Technical Services team, I helped reshape both the content and timing of these briefs. We looked to global frameworks, such as the RIBA Plan of Work, and adapted them to fit the kinds of mixed-use, design-led projects we were delivering at Trojena.

That shift led to better coordination, fewer false starts, and more productive collaboration between design, engineering, and delivery teams.

If you’re putting together a detailed design brief, remember: your job isn’t to lock in materials, finishes, or MEP systems. Your job is to frame the key decisions. The decisions that shape the concept and set up your project for success.

What Goes Into a Quality Design Brief?

I’ll dive deeper into each of these sections in future articles, but here’s a quick look at what a complete, actionable design brief typically includes:

1. Project Overview – This sets the tone. It captures the big picture: your vision, objectives, and what’s driving the project.

2. Site Context – Maps, access, topography, and environmental considerations that will shape the physical design.

3. Programmatic Requirements – A clear outline of uses and spaces, including both summaries and space schedules.

4. Design and Planning Criteria – Expectations around layout, massing, adjacencies, and character.

5. Technical and Sustainability Criteria – Early technical assumptions, MEP considerations, and sustainability goals.

6. Operational and Implementation Framework – Phasing plans, delivery timelines, and the rollout of the project.

7. Stakeholder Engagement Summary – Documentation of consultations with key parties and any community input.

8. Appendices – Supporting data, imagery, precedent examples, or anything else that adds clarity.

Start with what you already have, market research, feasibility analysis, planning documents, and organize it into a format that your team can work with. You don’t have to overengineer it. Be clear, honest, and specific where it matters.

At Trojena, we developed a standard design brief outline and a set of standard narrative language that the team could adapt across various asset types. But even then, every brief had to be tailored to the project’s specific scale, phase, and context. That’s the point, it’s not a form to fill out. It’s a tool for thinking.

Bringing It All Together

The detailed brief is what connects strategy to sketch. It ensures that information backs ambition. It provides your team with a shared foundation and helps prevent drift, whether in design, delivery, or dialogue with stakeholders.

If your goal is to do more than sketch out a big idea on a whiteboard, the detailed brief is your next step. In future post, I will be expanding on some of the key elements of an effective design brief.

Stay tune for more.

Leave a comment