What did you say is going in the building?

You are already halfway through the meeting when someone finally asks the right question: “What exactly is going into this building?” It stops the room. Not because your team doesn’t have ideas but because you don’t yet have a clear, shared answer. Everyone had been talking about vision, impact, and budget. But one of the most basic questions is unanswered, “What needs to be in the building?”

Why Programmatic Requirements Matter

You can’t design what you haven’t defined.

Programmatic requirements are the backbone of a real estate project. They are where big ideas meet real-world needs. In any well-run project, they appear early in the form of a clear and critical component of a project’s design brief.

This part of the brief doesn’t need to be fancy. It needs to be technical in nature and precise. It clearly outlines what the project entails, its scope, operational requirements, and what success will look like in terms of physical space and operational functionality.

Breaking Down the Qiddiya Arena Brief

At Qiddiya, we employed this approach to help define the Qiddiya Arena, a national-scale venue designed to host a range of events, including sports, concerts, conferences, and more. The programming for that project encompassed every primary use, seating tier, spatial layout, technical system, circulation route, and conversion mode imaginable. What helped was breaking it all down into a few core components.

We started with use types, not just sports, but different event categories with distinct requirements: basketball, ice hockey, handball, concerts, family shows, conferences, and even esports and mixed-use event formats. For each, we defined ideal capacities, spatial needs, and technical setups.

Then, we examined the various modes of operation, including full-arena events, partial-seating concerts, standing-room-only shows, and MICE configurations. That dictated a lot about how the seating bowl needed to be designed, where curtains and partitions would be placed, and how lighting and sound would need to be adapted.

Beyond the arena floor and seating, we outlined every front-of-house and back-of-house component in the program, including VIP lounges, concourses, food and beverage points, merchandise areas, prayer rooms, medical zones, loading docks, rigging and tech support, and broadcast setups. Nothing was left vague.

Getting the Details Right – Detailed Building Programs

After outlining the main elements, an effective design brief provides a comprehensive listing of the individual spaces and facilities required, often referred to as a Building Program or Functional Requirements. The building program is a detailed spreadsheet that breaks down all the project’s components, categorizing the primary elements by specific uses or unit types, each with key metrics.

For every space or use, the Building Program should list:

- Name/Type: What the space is

- Description and Function: What happens in that space

- Size/Area: Target size or capacity

- Configuration/Orientation: Any specific layout or adjacency needs

- Quantity: How many of that type

- Product Mix or Category: Where applicable, such as retail categories or housing types

Providing this specificity sets clear design parameters and supports area budgeting. For instance, a mixed-use tower might allocate 40% to office, 25% to residential, 10% to retail, and the remainder to lobbies, amenities, and circulation. That breakdown shapes how the building is stacked and how each space supports the larger vision.

A Word of Caution Related to Size/Area Definitions

It only takes one misunderstanding to throw a project off course.

I’ve seen it happen: a beautifully detailed building program is handed off to the design team or priced by the contractor, but no one clarified whether the area numbers were gross or net. Weeks go by. Designs are produced. Costs are estimated. And then someone asks a fundamental question: “Wait… are these usable areas or gross?”

Cue the scrambling.

When it’s unclear whether a program is based on Gross Floor Area (GFA), Net Usable Area (NUA), or Net Leasable Area (NLA), you’re setting up your team for confusion, inefficiency, and potentially serious financial mistakes. If a residential developer uses gross numbers to price the interiors, they may underestimate the construction cost per unit. If an architect assumes net areas and designs too compactly, they could shortchange essential circulation and support space. Either way, the result is wasted time, blown budgets, and compromised design integrity.

Balconies and terraces are another frequent culprit. Are they included? Is it 100% or discounted? Everyone seems to have their own understanding of what the numbers mean. That’s why even small features like these must be clearly listed in the space program, with adjustment factors stated upfront. For example, count a 100 SF balcony at 50% toward net saleable area if that aligns with local market practice, but document it.

To avoid these pitfalls, define your terms early and use a standard that everyone recognizes. ANSI/BOMA standards for commercial and mixed-use properties, or RICS Property Measurement Standards for global consistency, provide solid starting points. Choose one. Reference it in your space summary. And ensure that every team member, whether they’re designing, leasing, or modeling financials, understands what those numbers represent.

The takeaway? Precision in area definitions isn’t just technical nitpicking. It’s the foundation for good design decisions, solid financial models, and clear communication across the team. Make your assumptions explicit. Label every number. And don’t wait for someone else to ask the question. By the time they do, it might already be too late.

Planning for Relationships and Adjacencies – Programmatic Relationships

Knowing what spaces are needed is one thing. Understanding how they relate to each other is what turns a checklist into a design.

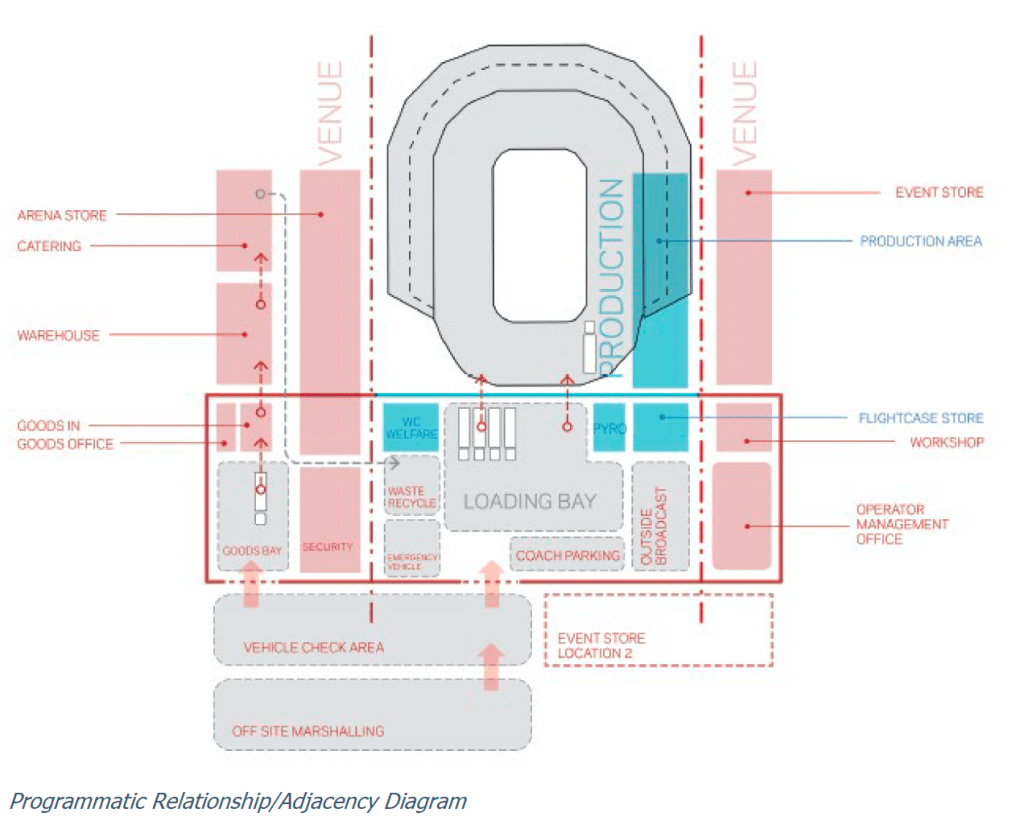

In mixed-use projects, those relationships are often where the magic, or the mess, happens. Residential areas may need separation from noisy commercial fronts. Hotels might benefit from adjacency to a conference center. Loading zones should not impede access to public plazas. These relationships can be illustrated through adjacency diagrams and circulation maps, but defining them in writing is also key.

We did this at Qiddiya by mapping user flows: who enters where, who shares elevators, and who never crosses paths. By thinking through those flows up front, the design progressed with clarity rather than contradiction.

Establishing Key Design Criteria – Success Factors

Design isn’t just about area takeoffs and room counts. It’s also about atmosphere, performance, and operational logic. That’s where design criteria come in.

At Qiddiya, some of our key drivers were:

- Acoustic quality and control across event types

- Lighting flexibility to match sport, performance, and corporate events

- Cultural responsiveness in layout and amenities (like gender-segregated seating)

- Conversion time between events and minimization of downtime

- Clear sightlines (measured by “C-values”) for every seat

Beyond that, a good brief includes context, constraints, regulatory considerations, and phasing strategy:

- Site context (climate, views, adjacencies)

- Regulatory framework (zoning, height limits, parking ratios)

- Site planning opportunities and constraints (slopes, access points, existing utilities)

- Aesthetic goals and design character (should it blend, stand out, reference heritage?)

- Phasing timelines (what gets built when, and how early phases stand alone)

- Calling these out early provides the team with guardrails without limiting creativity.

Engage the Subject Matter Experts

We ran into a different kind of challenge at Trojena. With such an aggressive schedule, we had to begin design work on the hospitality assets without having operators signed. That can be a recipe for disaster. But NEOM’s hospitality division helped fill the gap.

Morgan Tuckness, their head of design and architecture, acted almost like a surrogate operator. Her understanding of what brands like Chedi or Six Senses expect allowed us to anticipate layout needs, room sizes, the number of keys, amenities BOH requirements, and service flows. We were able to draft briefs that were approximately 80% aligned with the eventual operator standards, which resulted in far fewer revisions down the line.

A similar thing happened with the Qiddiya Arena. I had the opportunity to work closely with Tim Brouw, who has led planning and delivery for some of the world’s most complex sports venues, ranging from Olympic stadiums to FIFA World Cup sites.

Even with that kind of deep expertise on the team, we didn’t wing it. We brought in third-party subject matter experts with day-to-day operational experience to review and help refine the arena program.

These people knew what it takes to flip a venue from ice hockey to a concert overnight. They had seen what fails in real venues, such as circulation bottlenecks, under-designed loading areas, and misaligned concourses, and they knew how to avoid repeating these mistakes.

If your team doesn’t have someone who lives and breathes the asset type every day, get one. Whether it’s arenas, hotels, labs, or schools, someone out there is spending eight hours a day thinking about how these places function. That’s the person you want writing or reviewing your program.

Final Thoughts

A solid Building Program isn’t just a list of spaces. It’s a framework for design decisions. It aligns vision with operations. It anticipates conflicts before they happen. It turns aspiration into architecture.

If you’re pulling together a design brief for your project, start by answering this: What spaces do you need, how big are they, what do they need to do, who do they serve, and how do they need to relate to each other?

Then, go deeper.

Where are the pressure points? What are the key moments in circulation? How will different users interact with the building? What needs to flex over time?

Get as clear as you can upfront.

Because once construction starts, changes get expensive. And once the building opens, the program becomes real. So, make it right before it gets built. That’s where good design starts.

Leave a comment