The design was beautiful. It was thoughtful, contextual, and ambitious. The kind of work a team can be proud of.

However, the first detailed cost estimate was 28% over the assumed budget. That’s when the finger-pointing started. Was it the architect? The estimator? The owner?

No. The real problem was that the development team didn’t build the budget at the same pace as the design. It was a placeholder, not a process.

If you’ve been there, you know how fast optimism can turn into rework. That’s why getting your arms around a budget early is one of the most strategic things you can do.

The moment you decide what you want to build, the next question is simple: can you afford it? That’s the heart of every development project. Whether planning a single building or a 500-acre community, you must align your ambition with your financial capacity. And that alignment doesn’t happen by accident. It takes structure, iteration, and a straightforward process.

This article is about the budgeting process.

It’s about translating a vision into a viable budget. A budget should reflect your goals, the market, and the realities of what things actually cost. If you’ve already built out your design program (see Crafting a Comprehensive Building Program: Key Insights), then now’s the time to make sure your design ambitions and financial constraints are moving in the same direction.

Let’s break it down.

A Budget Is Not a Cost Estimate

People mix these up all the time. Based on drawings and scope, a cost estimate tells you what something will cost. A budget is a financial target. It sets a cap, ideally, before the design starts, so you know the limits you’re working within.

You’re effectively shooting in the dark if you wait until the design is underway before defining the budget. That’s how you end up with chaos, confusion, and scope that needs to be cut late in the game.

Setting a budget early, even if it’s imperfect, gives your team a framework, allows for tradeoffs, and creates discipline.

Top-Down vs. Bottom-Up: You Need Both

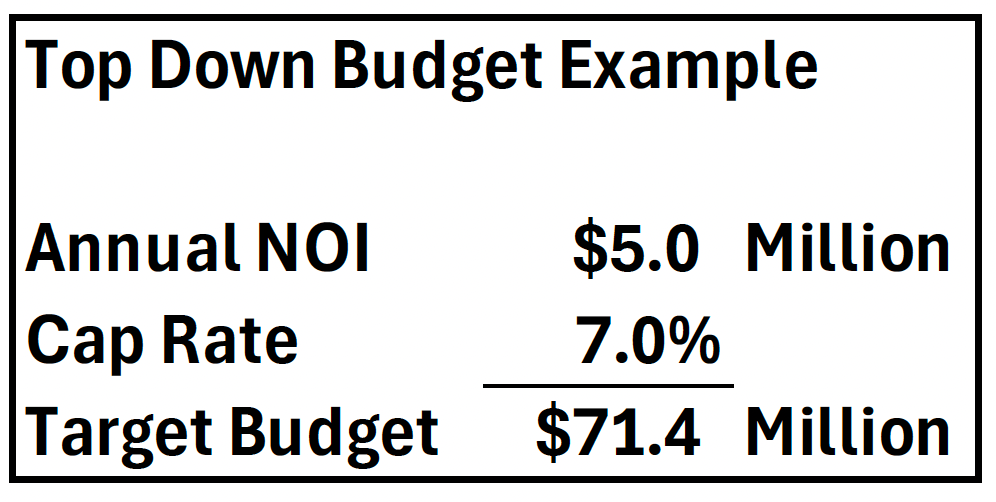

Top-down budgeting starts with what you want out of the project. Let’s say you expect $5 million in annual NOI from a rental project, and you’re targeting a 7% return on cost. That means you can afford to spend about $71 million all-in. That’s your top-down cap.

Bottom-up budgeting starts with the program and estimates each component: site work, shell, MEP, interiors, fees, contingencies, etc. It tells you what it will most likely cost to build what you want and need.

And here’s the thing: those two numbers rarely match the first time around.

That’s where the real work begins. You iterate. Adjust scope, quality, phasing, timing, or returns until the two sides of the equation align. That’s the core of disciplined development.

The Budget Structure: Start with Line Items

Every project, regardless of size, deserves a clear, structured budget. That starts with breaking it down into logical categories. These categories vary by project type, but the principle is to make each cost visible and accountable.

For Land Development:

- Land Acquisition: Purchase price, legal fees, title insurance, due diligence, closing costs, and interim holding costs like taxes and insurance.

- Site Preparation: Tree clearing, demolition of existing structures, rough grading, erosion control, and environmental remediation if needed.

- On-Site Infrastructure: Internal roads, sidewalks, water lines, sewer, electrical, stormwater systems, gas lines, and telecom/fiber conduits.

- Off-Site Improvements: Roadway turn lanes, sewer pump stations, intersection upgrades, utility extensions, or improvements required by local jurisdictions.

- Landscaping & Amenities: Common area landscaping, irrigation, parks, playgrounds, walking trails, street furniture, and signage.

- Horizontal Construction Contingency: Reserve funds for site-related unknowns like unsuitable soils, rock removal, or utility conflicts.

- Planning & Engineering (Soft): Master planning, civil engineering, surveying, environmental studies, traffic studies, and geotechnical reports.

- Permits & Fees: Entitlements, rezoning, subdivision approvals, utility connection fees, impact fees, and plan review charges.

- Legal, Accounting, and Insurance: Easements, HOA documents, project contracts, financial controls, and liability coverage.

- Developer Fee: Fees for managing the entitlement and development process, often 3–5% of total project cost.

For Building Development:

- Demolition & Site Prep: Clearing the footprint, sheeting/shoring, excavation, and grading for foundations.

- Foundation & Structure: Concrete work, steel framing, slabs, bearing walls, and everything from the ground to the top floor structure.

- Vertical Circulation: Stairs, elevators, and mechanical lift systems.

- Envelope: Exterior cladding, curtain walls, windows, insulation, waterproofing, roofing, and vapor barriers.

- Interior Construction: Partitions, drywall, doors, hardware, ceilings, shared lobby and corridor finishes.

- Interior Finishes: Flooring, paint, tile, fixtures, and specialty trim—especially in shared or public areas.

- Mechanical Systems: HVAC units, ductwork, controls, and building-wide ventilation systems.

- Electrical & Lighting: Power distribution, lighting fixtures, switches, panels, and emergency backup systems.

- Plumbing & Fire Protection: Water supply, sanitary and storm drains, fixtures, and sprinkler systems.

- FF&E: Fixed furnishings, equipment for kitchens or retail, casework, and specialty installations.

- Site Improvements: Final grading, planting, site lighting, curb cuts, and parking areas.

- General Conditions: Temporary utilities, site security, construction offices, dumpsters, and job site logistics.

- Contractor Overhead & Profit: General contractor fees to manage subs and risk.

- Architecture & Engineering: All design team fees for architects, engineers, interior designers, landscape architects, lighting and acoustics consultants.

- Permits & Approvals: Vertical construction permits, plan review, inspections, and occupancy certificates.

- Legal, Accounting, Insurance: Construction draw management, wrap-up insurance, contract negotiation, project tax exposure.

- Financing Costs: Loan interest, fees, appraisals, third-party reports, and reserves required by the lender.

- Marketing & Leasing: Broker commissions, signage, marketing campaigns, website, sales office, or model units.

- Development Management: Internal or external fee to coordinate execution from design through construction and delivery.

Financial Returns by Asset Type

Understanding return expectations early in the process can make or break feasibility. Most institutional investors and developers use these as target, unlevered returns:

- Land Development: 20–30% yield on cost, 15–25% IRR

- Single-Family For-Sale: 12–20% yield, 12–18% IRR

- Multifamily Rental: 5.5–7.5% yield, 10–15% IRR

- Hospitality (Luxury): 8–10% yield, 15–20% IRR

- Office (New Build): 6.5–8.5% yield, 12–18% IRR

- Mixed Use: 12–18% IRR depending on use mix and phasing

Returns will always be influenced by a mix of factors, including location, entitlements, complexity, phasing, market cycles, financing, and the developer’s risk tolerance.

Personal Story: Celebration’s Showcase Village

At Celebration, we weren’t just rethinking neighborhood design. We were trying to change the local construction culture, which meant moving away from Central Florida’s stucco and tile defaults.

We benchmarked historic Southern towns and brought in top architects. We didn’t want pastiche. We wanted integrity. We wanted the streetscape to feel walkable and rich in character.

To make that real, we built Showcase Village, a group of demonstration homes designed by skilled architectural firms like Historical Concepts, John Reagan Architects, and Ike Kligerman. Each design followed a shared brief but brought its own lens and personality. The houses weren’t a theoretical design guide; this was architecture you could walk through.

Historical Concepts’ design for the Coastal Showcase Village House emphasized authentic Southern vernacular with deep porches, horizontal lap siding, and shutters. Historical Concepts specified 5V Crimp metal roofing, a material frequently used in several towns we visited and studied on our benchmarking tours. We believed in its look, durability, and design precedent. Based on our discussions with builders who used 5V Crimp roofing on their houses, the cost was reasonable from a lifecycle perspective.

Given that 5V Crimp roofing was seldom used in Central Florida, we reached out to a potential vendor to better understand the cost. When the numbers came back, they seemed highly inflated. Why? The “Disney effect.” Vendors saw the name and added premiums. We called it out. We pushed back. We found a new vendor who understood the intent and delivered the product for a fair price.

That small win signaled something bigger. It showed the market that we meant business, that authenticity was non-negotiable, and that we were paying attention. It also showed that budget development had to anticipate not just materials and labor but also perception.

Personal Story: Trojena’s Budget Reality

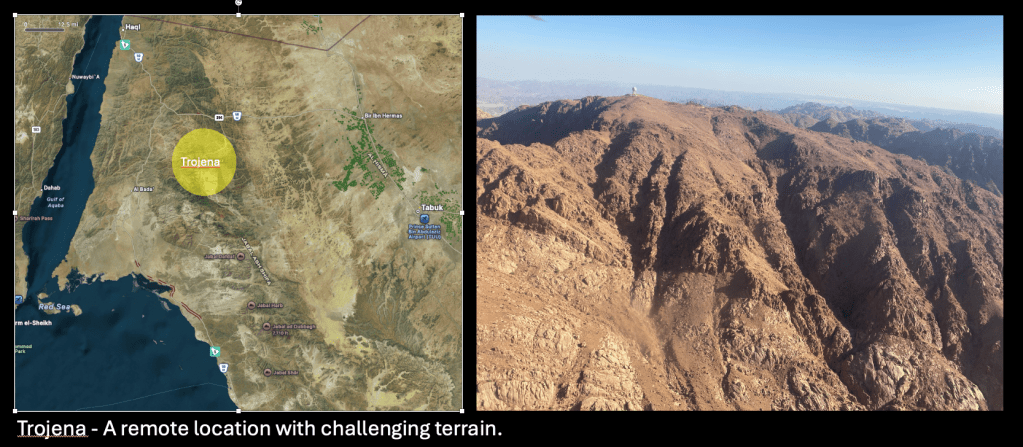

Trojena was a different world. Literally.

We often said we were “building the nearly impossible in the nearly inaccessible.” That wasn’t too much of an exaggeration. It became something of a mantra. We were tasked with developing destination resort assets near Jebel al Lawz, a mountain in the Sarawat Mountains. The site is remote with high-elevation terrain, no real precedent, and few physical or logistical parallels. From day one, we knew this wouldn’t be business as usual. Our early budget estimates pulled unit costs from comparable assets in Riyadh and Jeddah. Those numbers collapsed under scrutiny.

Why? Trojena isn’t flat land in or near a major metropolitan area. It is a remote, sculptural retreat embedded into steep cliffs. The design ambition was sky-high, and execution would be anything but standard. Before building the actual projects, we had to build roads to get to the sites. Labor would live in temporary camps. Materials had to be trucked in from hours away. We were managing architecture, logistics, and survival all at once.

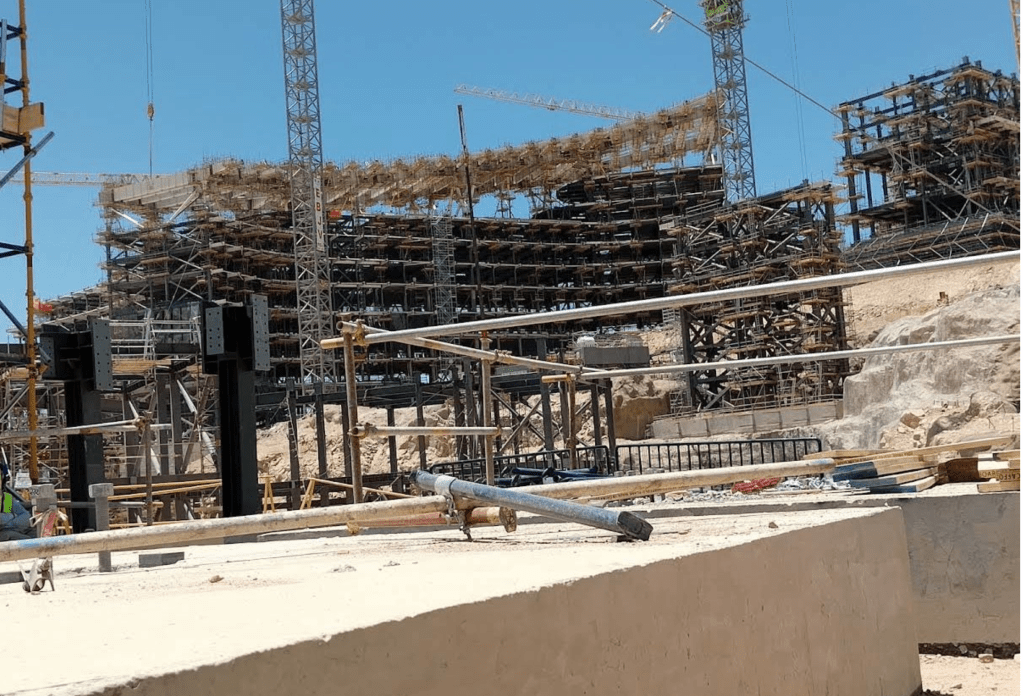

Cost per square meter benchmarks? Useless. We rebuilt the budgets from the ground up. We included access roads, helicopter pads, temporary staging zones, logistics coordination, and storage yards. We had cost premiums for the site location, the site characteristics, and the complexity of the designs. Rather than using a single cost per square meter for the entire building, we categorized the various rooms and spaces by level of importance and required fit and finish, front of house versus back of house, spas versus lobbies, hotel suites versus work rooms, and assigned a different cost factor for each of them. We layered in premiums for engineering, labor availability, and compressed schedules.

We incorporated a healthy contingency into the initial budget because we knew the project would demand flexibility. Even so, as the design evolved and ambition increased, the estimates began to outpace the original allowances. The complexity of the structures, the site conditions and location, and the speed required for delivery all pushed the numbers.

The team leaned in and sharpened its pencils. Internal and external collaborators, designers, engineers, and contractors worked together to reconcile design intent with cost implications. That alignment was essential.

Several of the most iconic assets, including the Ski Village by Aedas Architects and the Vault by LAVA, are under construction today. Getting to this point took relentless iteration, trust, and clarity between vision and execution.

That experience made one thing clear: if your site is hard to reach, your budget must reach further. You must plan for what you’ll build and what it takes to make building possible.

Contingencies: Apply Them Smartly

A good contingency plan is like a shock absorber. It doesn’t prevent surprises, but it helps you absorb them without crashing the project. A big mistake I have seen on several projects is applying a single contingency percentage across the entire budget. It’s lazy, and it hides risk rather than managing it.

Instead, tailor contingency line by line.

- Predictable scope (standard finishes, permitting, utilities): 2–5%

- Material cost volatility (steel, copper, glass): 10–20%

- Design not yet finalized (MEP systems, custom facades): 10–15%

- Unknowns (geotechnical surprises, soil remediation): 15–25%

- Owner-driven decisions or scope creep potential: 10–20%

Track contingencies in a separate column. As the design solidifies and you lock in pricing, reduce contingency allowances. Reallocate as needed. Don’t eliminate them; make them more precise as you have more information.

This line-item approach builds transparency and trust. It also helps stakeholders understand where the biggest unknowns live and that you are managing them.

Document Everything

Budgets live and die on clarity. If someone looks at your spreadsheet and can’t tell where the numbers came from, that’s a problem. Every cost should be more than a number. Each line item should be a statement of intent. A record of assumptions. A story that explains itself.

Let’s say you budgeted $1.2 million for site utilities. Someone will ask: what’s in that number? Did it come from a contractor quote? A unit cost benchmark? Does it include contingency? Are tap fees separate?

The most reliable budgets are the ones where you can track the origin of every figure. You don’t need to write a novel. But you do need to be able to say:

- How did you get the number

- What does it include (and doesn’t)

- What assumptions were made

- What stage of design it reflects

- What the basis of the estimate was (e.g., RSMeans, subcontractor quotes, recent projects)

Good teams create space for this in the budget, either with a comment column next to each line item or in a companion “basis of estimate” sheet. Great teams review these notes regularly and refine them as the project progresses.

This practice helps you in three significant ways:

- It protects you. If costs change or designs shift, you can retrace your steps and adjust purposefully.

- It builds trust with investors, lenders, and partners. When you show that your numbers have a backbone, they listen differently.

- It makes your team smarter. Documentation becomes institutional memory. When someone new joins the project six months in, they don’t have to guess why the landscaping budget is $300K. It’s there in writing.

Good documentation doesn’t have to be complicated. It just has to be consistent. Over time, it turns a spreadsheet into a shared understanding, making all the difference.

Use the Right Resources

A budget doesn’t just come from inside your team. You also need to know where to look for credible, up-to-date benchmarks. So, where do you turn when trying to figure out if your assumptions, especially on returns, are realistic?

Start here:

- ULI (Urban Land Institute) Reports: Their Emerging Trends in Real Estate and market outlooks offer well-researched insights into investors’ expectations across asset classes.

- PWC Real Estate Investor Surveys: These surveys break down return expectations by property type and investment strategy.

- CBRE, JLL, and Cushman Investment Reports: These global real estate advisors publish quarterly and annual return expectations, yield-on-cost benchmarks, and cap rate trends.

- NAHB (National Association of Home Builders): For residential and land development, NAHB offers studies on typical cost-to-build, margins, and developer expectations.

- HVS and Hospitality Net: These are your go-to resources for hotel projects.

Each of these resources serves a different purpose. Together, they help you triangulate what’s reasonable, what’s ambitious, and what’s out of bounds. The trick is not to rely on any one source but to use several, compare their data, and interpret them in the context of your specific project.

Smart budgeting blends real project data, professional judgment, and industry benchmarks. That’s how you move from a placeholder to a plan.

Final Thought

Budget development isn’t just a financial exercise. It’s a design and strategy tool that tells you if your vision is feasible, shows you where to adapt, and keeps your team honest throughout the process.

Proper budgeting isn’t just about dollars. It’s about discipline. It’s about translating possibility into a path. You won’t have to pause when you get the question, “What is the budget?”. You’ve done work to build both top-down and bottom-up. You’ve documented your assumptions, accounted for uncertainty, and aligned your design with your financial goal. You’ll have an answer.

The best budgets don’t just show what you can spend. They show you what’s possible and how to get there with clarity, conviction, and confidence.

Leave a comment