We are impatient by nature. We want everything today, if not yesterday. But real estate development doesn’t work that way. As the old saying goes, “Rome wasn’t built in a day,” and neither are great communities.

As part of the Design Brief, the phasing approach should be clearly described to set expectations and guide execution. This section of the design should outline how the project will unfold over time, what elements will be delivered in each phase, and how each phase contributes to the overall vision. Being explicit about phasing helps stakeholders understand what to expect and when, reducing confusion and misalignment. It also allows the project team to focus on properly allocating resources, setting priorities, and coordinating efforts around defined deliverables. Without this clarity, it’s easy for ambition to outpace feasibility or for different parties to develop conflicting assumptions about timelines and scope. That is why a proper phasing strategy and execution isn’t just helpful. It’s essential.

Large-scale mixed-use community developments are rarely built all at once. Instead, they are typically broken into multiple phases to manage scope, risk, and financing. A well-crafted phasing plan lays out how the project will be sequentially implemented, with each phase providing value on its own. One key challenge is ensuring each phase provides a useful, completed product that is both economically viable and functional.

In practice, each phase should deliver a self-sufficient mix of elements: housing, public space, and ideally, some retail or community-serving use. It must feel alive before the rest of the project comes online. And it must demonstrate the promise of what’s to come. A phase is more than a construction milestone. It is a microcosm of the entire community.

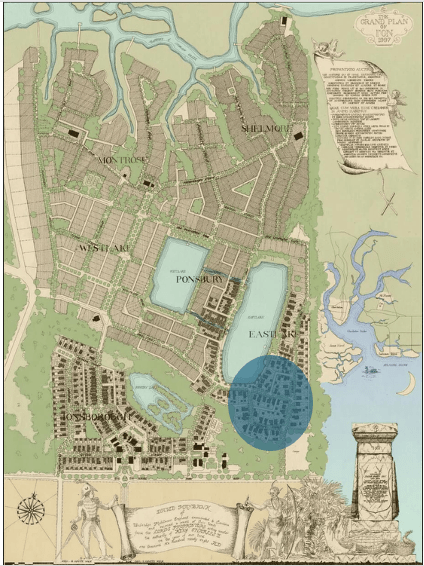

Every project I have worked on, including Celebration, I’On, East Beach, required a different approach to phasing. Each one had its own financial constraints, market conditions, mix of uses, level of innovation, and complexity. However, each illustrates what’s possible when phasing is treated as a strategic design and development tool.

Celebration: Front-Loading the Downtown

When you develop under the Disney name, expectations are extraordinary. We couldn’t talk about the vision for Celebration’s town center. We had to build it. Right away.

At Celebration, that meant front-loading the downtown: 150,000 square feet of commercial space, with apartments above and a cast of top-tier architects designing civic anchors—Venturi & Scott Brown, Michael Graves, Cesar Pelli, Philip Johnson.

The buildout wasn’t random. A clearly defined mandate guided it: Make it special. Make it memorable. Make history. Make it replicable. Make it consistent with the Disney brand. And yes, make it profitable. Each of those goals had architectural, cultural, and operational consequences.

We weren’t just designing spaces. We were curating experiences. From the pedestrian-friendly scale of the streets to the carefully considered mix of uses, every decision reinforced the core idea of Celebration as a complete and functional town from the start.

That meant making sure the streets were legible and welcoming, that housing was walkable to shops, dining, and parks, and that the design character was instantly recognizable and grounded in timeless principles. The civic buildings were anchors, not afterthoughts. They helped lend credibility to the vision.

And it paid off. Over 5,000 people attended the Founders’ Day Drawing, and we received over 1,200 deposits. Thanks to a front-loading downtown, we were able to achieve what very few developments ever do, essentially selling out our first two phases of homesites in a single day. The project made headlines around the world. Two books chronicled the process. Celebration became its own attraction. Tours poured in from developers, architects, and municipal leaders. The downtown was more than an amenity; it was a sales engine.

Associated with Disney, Celebration could have been a marketing gimmick. Instead, it became a lesson in what happens when expectations drive purpose and purpose drives execution. Every element reinforced the brand, and every sale reinforced the vision. That’s why the initial downtown build wasn’t just smart. It was revolutionary. It shifted Celebration from a development to a destination, and those results proved it was the only way to go.

The early success wasn’t just a fluke. It resulted from an intentional strategy to demonstrate the development vision tangibly before asking the market to buy into it. People weren’t purchasing a promise. They were buying into something they could see, walk through, and experience.

I’On: A Proof of Concept for a Different Model

At I’On, we weren’t trying to meet expectations. We were trying to reset them. Conventional development in the late 1990s meant curvilinear streets, separated uses, garages up front, and little attention to public space. We rejected all of that.

To prove our approach worked, we focused early efforts on a tight area, a mix of lot types, a curated group of architects and builders, and a set of homes that didn’t just look good on their own but made the street better as a whole. We saw house facades as the interior elevations of outdoor rooms. We worked hard to get them to speak to each other.

We didn’t release the first homesites to strangers. They were released to a group of early believers we called Founders. These early adopters joined our pre-development educational events about the project’s vision and location, and many publicly supported it during municipal approval hearings. These families understood the vision. They became advocates. They brought others along.

This focus on phasing the development of the project so it was a complete, but small, physical manifestation of the urban and design principles paid off in several ways. We had a location that could be photographed for ads and marketing materials. People interested in building a home and living in I’On but were still skeptical about the concept could walk down a complete street and get a first-hand understanding of the environment we were attempting to create. We didn’t have to rely just on renderings and models anymore. Also, construction activity was concentrated in a relatively small area, so we could complete it sooner and reduce the nuisance of ongoing construction activity.

Some of my favorite words of wisdom related to community development come from Vince Graham, one of the Founders of I’On, his father Tom, and his brother Geoff. Vince’s research on the sales and marketing of communities was that a conventional approach was to promote “Privacy and Exclusivity”. The problem with that approach is that each time you sell a lot and build a house, you are taking away or degrading the value proposition you are promoting. Instead, if you promote “Community”, each time you sell a homesite, build a house, and have a new family move in, you add value to and enhance what you are promoting.

I love the story one of my I’On neighbors told me about his introduction to I’On. He had been reading about and hearing about this place called I’On for several months. Relatively content where he and his family lived then, he had no interest in house shopping. One day during his lunch break, he drove through this first completed section of I’On, which we now jokingly refer to as I’On’s “Historic District”. Seeing what he saw and, perhaps more importantly, feeling what he felt, he instantly understood what I’On was all about. He headed to the onsite sales offices (we were in construction trailers then) to see about available homes and homesites. He bought a spec house across the street from my house. Years later, they purchased another homesite in a future phase and had a house custom-designed and built for their family.

As that phase matured, lot values jumped. Two lakefront lots priced initially at $90,000 were re-listed at $300,000 and sold within a day. That kind of value creation came not from hype but from delivering a built environment with which people could instantly connect.

As we proceeded with the development of I’On, we followed this approach of developing homesites and building homes in relatively concentrated areas. This strategy worked well for the most part, but we ran into some issues regarding the mix of lot types and related price points. We always aimed to maintain a good cross-section of lot types, sizes, and price points to appeal to the broadest possible market.

However, our land takedown agreement required us to move from east to west in contiguous sections. As we reached the area that would become Westlake, the lots carried a premium due to their location on the water. These were among the highest-priced homesites in the community. With fewer buyers at the top of the market, sales slowed. While our gross revenue was comparable to previous years, the pace of building activity dropped, and it took significantly longer to complete this section.

Once we worked through those high-end lots, we moved into portions of the site with a better mix. Sales pace rebounded, and building activity picked up. The takeaway: always maintain diversity in your product offering. If everything in a phase is high-end, you limit your buyer pool and risk stalling momentum. Momentum is currency in community development; everything else becomes harder once it slows.

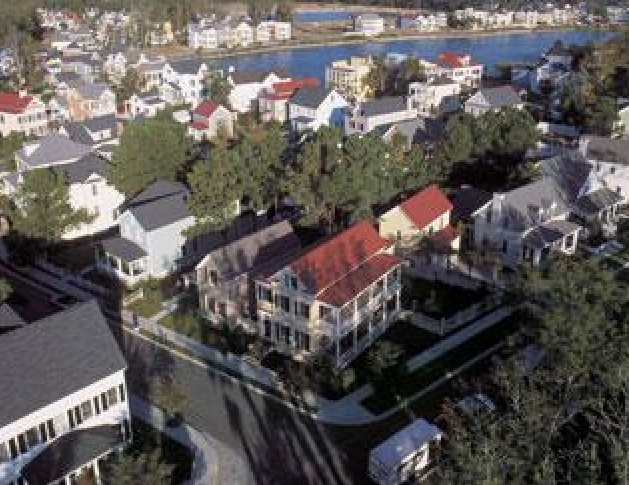

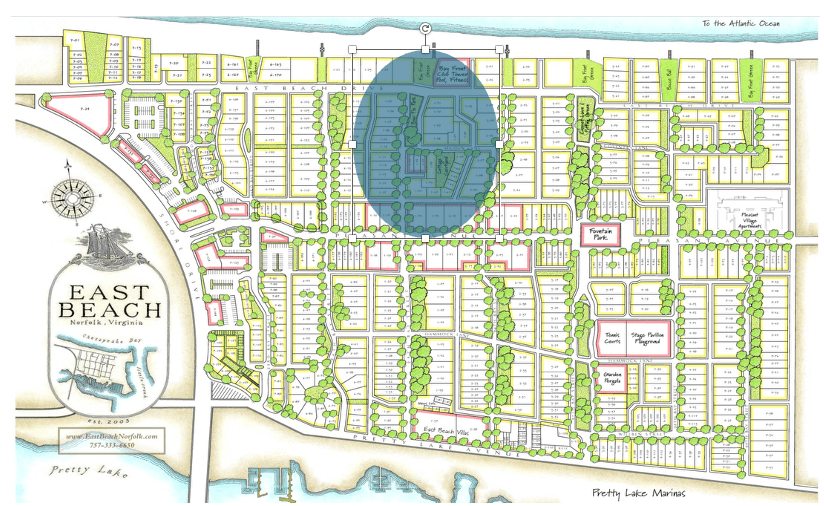

East Beach: Rebuilding Trust, Block by Block

In Norfolk, Virginia, East Beach wasn’t about launching a new brand. It was about reversing the decline. The site had been home to thousands of post-WWII temporary housing units that had, over time, decayed into some of the city’s most dangerous and neglected housing. The area’s reputation kept investors, residents, and even pizza delivery away.

But the City of Norfolk had a vision. And East Beach became the vehicle to bring it to life.

We knew we needed a dramatic and credible first step. We had to turn perceptions around and give people something to believe in. So, we concentrated development in a single, walkable block. That meant 18 architect-designed and fully furnished homes, three pocket parks, and a beautifully executed Bay Front Club as an early civic anchor. We intentionally limited access to the site during construction to ensure that the first public experience would be a complete one.

That public unveiling came through Homearama in 2004, a home show sponsored by the Tidewater Builders Association. Over 2.5 weeks, more than 125,000 people walked the neighborhood. They didn’t just see renderings or models—they walked streets, stood on porches, and watched kids play in the parks. It was an emotional and tangible demonstration of what East Beach could become.

Another impact of delivering a complete and compelling first phase was its dramatic effect on land value. Among our most desirable assets were a handful of homesites directly on the Chesapeake Bay. Even before development began, these waterfront lots held intrinsic value, with initial pro forma appraisals estimating them at around $350,000 each, which was already considered aggressive for the area at the time.

Some of the development team’s partners pushed to release the lots early to generate positive cash flow. I disagreed. If we waited until the first phase was complete, we wouldn’t just be selling waterfront property; we’d be offering lots in a fully realized, attractive neighborhood. That distinction would make all the difference.

When the time came to release three of the waterfront lots, we weren’t sure how to price them. If they were worth $350,000 before East Beach took shape, what would they be worth now? Surrounded by finished homes, public spaces, and civic infrastructure, they carried a different kind of value.

We opted for a sealed bid process with a $650,000 minimum bid. The outcome spoke volumes. Each lot received multiple bids. The winning bids averaged over $820,000, well above our earlier assumptions and a combined $1.4 million over our original projections.

That wasn’t a lucky break. It was a direct result of demonstrating value through execution. We didn’t just create a plan; we delivered a place. And the market responded accordingly.

Just as important, East Beach changed the narrative about what Norfolk could be. It was no longer just about removing blight. It was about reintroducing community, walkability, civic pride, and a regional coastal vernacular that respected the past while pointing toward a better future.

Phasing Fundamentals: What to Consider and Why It Matters

The goal of early phasing is simple: deliver a complete enough piece of the overall project to be solid proof of concept. A well-executed first phase can be economically, perceptually, and operationally transformative. Each phase must function as a small neighborhood, not just a construction zone.

This means:

- Mixing residential, civic, and maybe small commercial uses

- Delivering quality public space, even if it’s just a park or green space

- Making the streets feel alive and complete

When done right, phasing allows you to build infrastructure incrementally. Roads, water, storm, and power are delivered where and when they’re needed. Shared amenities can be front-loaded to benefit future growth. Each phase can respond to real-time feedback, adjusting based on demand, absorption, and user experience.

Strategic phasing also helps mitigate risk and manage investment. You’re not building a speculative city. You’re building a grounded, testable product that serves as proof of concept. Early success builds market confidence and unlocks access to financing for future phases.

Key best practices to keep in mind:

- Define clear phase boundaries: Determine what buildings, streets, and open spaces are included in each phase and ensure they form a self-contained district.

- Balance the mix: Include a range of uses from day one, including homes, parks, and civic elements to create vibrancy and functionality.

- Build the bones early: Horizontal infrastructure, utilities, and streets should be designed to support expansion. Don’t box yourself in with short-term thinking.

- Complete the phase: Avoid leaving unfinished gaps. Treat unbuilt areas with interim landscaping or temporary uses so the first phase doesn’t feel like a construction zone.

- Maintain flexibility: Markets shift, and community needs evolve. Your phasing strategy should be a roadmap, not a straitjacket.

These fundamentals apply to any project, regardless of scale. Whether you’re building 50 acres or 5,000, a smart phasing plan lays the foundation for everything that follows.

Delivery Timelines and Rollout

Long-range development means long-range planning. We’re often working with timelines that span a decade or more. A smart rollout strategy overlaps where possible: as Phase 1 is being leased or sold, Phase 2 might already be under construction or in for permit.

That sequencing supports cash flow. Early revenues can fund future work, and it also gives teams a chance to correct the course if needed.

Each phase needs its own operational launch plan, maintenance responsibilities, event programming, and marketing. You’re not just finishing buildings; you’re introducing new districts to the public. That means grand openings, targeted leasing campaigns, and seamless transitions from construction to community. These events help create and maintain a buzz about the project long after the first phase opens.

Stakeholder Alignment

Big projects involve many hands: cities, agencies, investors, community leaders, designers, contractors, and, most importantly, future residents. Getting everyone on board early makes things smoother later.

Public-private partnerships are common. That means shared decision-making. And shared accountability. Developers must often align their phasing strategy with public goals such as affordable housing or job creation to secure approvals and funding.

Community involvement doesn’t end once entitlements are secured. Ongoing communication, advisory committees, and transparency around schedules and construction are vital. People support what they understand, and they resist what surprises them.

Construction and Procurement Strategy

Phasing affects how you build. Some developers use one Construction Manager-At-Risk or a program manager across all phases. Others bid out each phase independently. Design-build can work well in some instances, particularly when schedule and integration are critical.

Procurement for long-lead items should be planned early. That might mean umbrella contracts for lighting or infrastructure that span phases, even if the actual installation happens over time. You want consistency but also flexibility to respond to new tech or trends.

Construction logistics can be tricky in active, occupied neighborhoods. Clear plans for access, safety, staging, and service continuity are needed. In some cases, temporary solutions, such as parking lots, pedestrian paths, temporary structures, and landscaping, can fill in gaps until the full buildout.

Final Thoughts

Phasing is not just an implementation detail. It’s a strategic framework. It affects what people see, what they believe, how they buy in, and how value is created. Done well, phasing gives you room to adjust. It keeps your team aligned. It lets your design vision breathe and evolve.

And it turns concepts into communities.

Leave a comment