From the outset, our charge at Celebration was clear: design and build houses that meet the community’s design vision and goals while also appealing to individuals and families from a programmatic, functional, and cost perspective. We couldn’t afford to let the houses look like every other Central Florida subdivision, nor could we design homes so architecturally pure that they ignored budget realities or how people actually lived.

The builder selection process

The Residential Builders Program we established initially included two national merchant builders, David Weekley Homes, headquartered in Houston, Texas, and Town & Country Homes, headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. These two builders would be responsible for most of the houses on our Townhouse, Cottage, and Village lot types. In addition, we selected eight custom builders, all based in Central Florida, for the larger lots.

We didn’t choose any of the builders based on the design quality of their previous work. Instead, we selected them for their proven track record in customer service, financial stability, and, critically, their willingness to take on something new and ambitious. Every one of them would need significant design support to meet the standards outlined in our Celebration Pattern Book.

To guide this process, two vice presidents of The Celebration Company, Don Killoren and Charles Adams, paired me, an architect with an MBA, with David Pace, a custom home builder who was also a CPA. David brought deep construction and cost knowledge. I brought a design-focused perspective and organizational skills. We had some intense discussions (and occasional knock-down, drag-out arguments) about how to proceed, but we respected each other’s expertise and shared the same goal. David and I “worked the problem”. Over time, we often found ourselves articulating the other’s point of view when making the case to our colleagues or the builders.

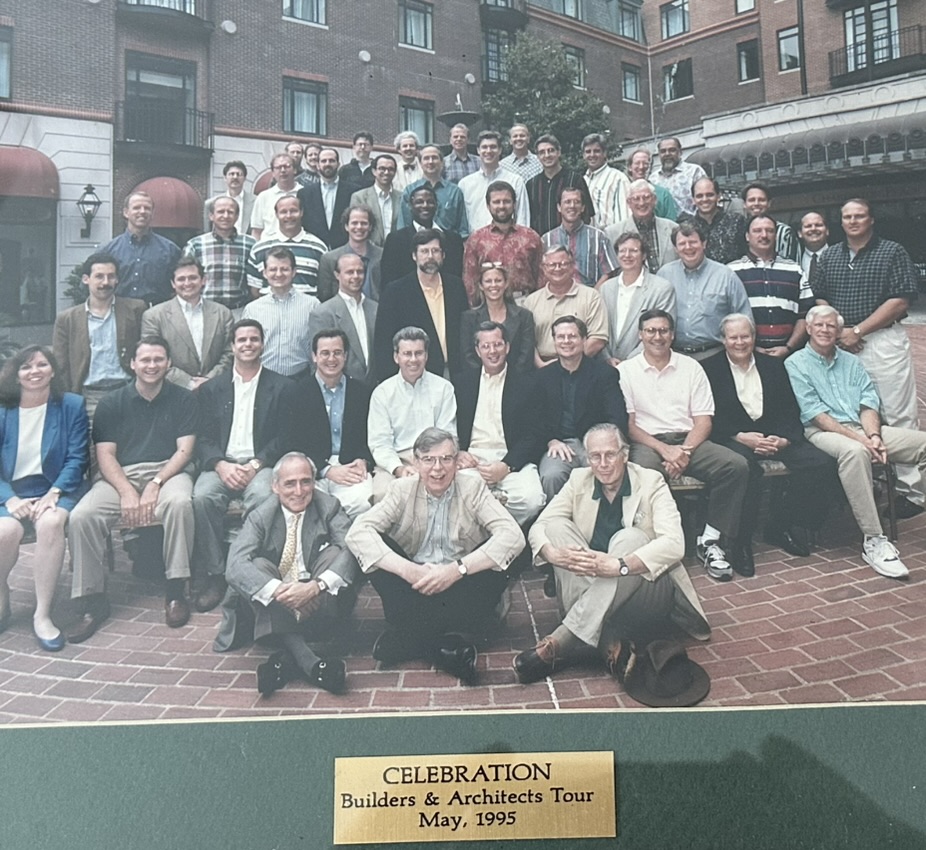

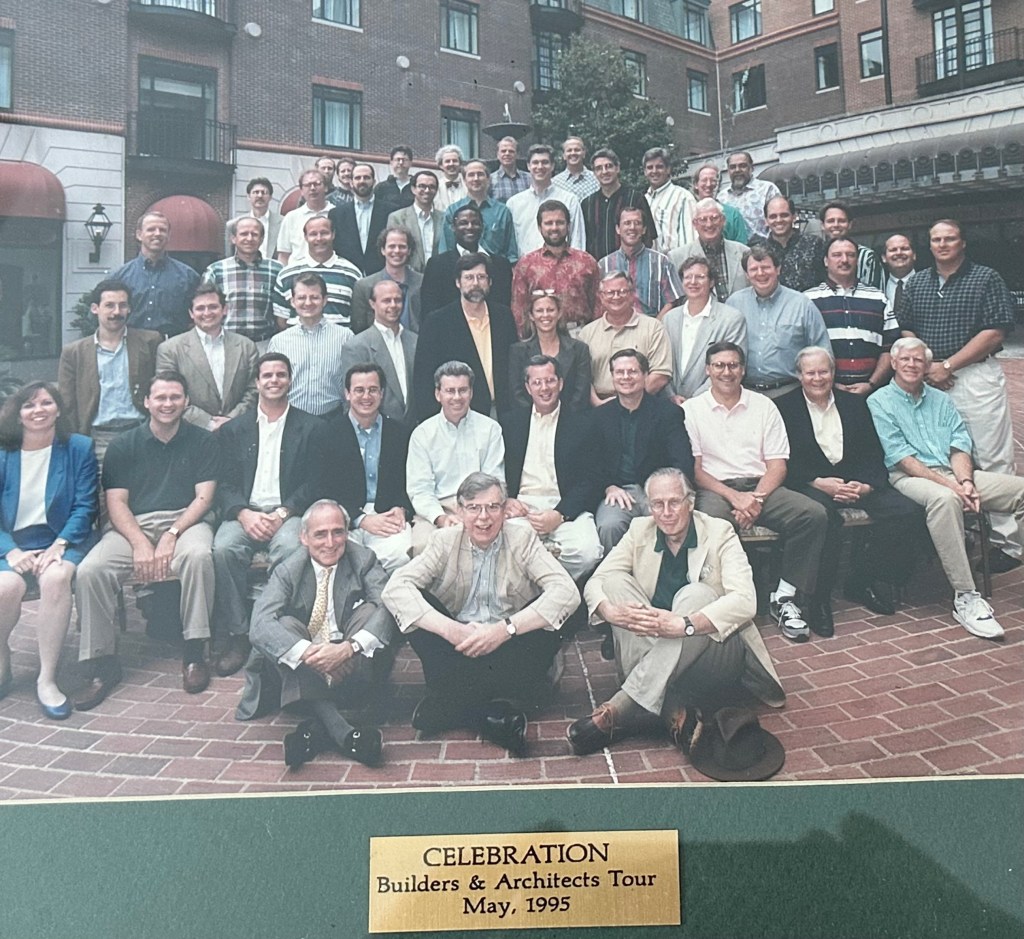

Educate: The Charleston Workshop, May 1995

The first step in our efforts to support the builders was education. We knew we couldn’t simply hand over the Pattern Book and expect compliance. In May 1995, we organized a two-day workshop called the “Celebration Builders & Architects Tour” in Charleston, South Carolina.

We invited:

- Members of the Celebration Development Team and several of Disney Development’s senior executives

- Robert A.M. Stern and Jacque Robertson, Celebration’s master planners, along with key members of their teams

- Ray Gindroz and Rob Robinson from Urban Design Associates, co-authors of the Pattern Book

- The owners or senior leadership from all the selected builders

- A handpicked group of architects experienced in designing houses in the Pattern Book’s architectural styles

Stern and Robertson walked everyone through the master plan, showing how Celebration’s streets, parks, greens, and building sites were organized. They used precedent images and illustrations to explain how the architecture, the streets, and the public spaces would work together as a coherent whole.

Urban Design Associates then detailed the six architectural languages in the Pattern Book. They explained in detail their historical origins, essential elements, and how they should be applied to specific lot types and locations.

We also wanted the architects to hear directly from the builders’ side. David Weekley, founder of David Weekley Homes, gave an unvarnished presentation about how production builders operate: cost constraints, scheduling pressures, and the metrics by which they measure success.

Inspire: Seeing the “Good Stuff”

At the end of each semester, my design studio professor, Professor Dripps, would meet with each of us individually. These were not quick check-ins. They were thoughtful conversations about what we had accomplished, where our work fell short, and what we needed to focus on to improve.

When it was my turn, Professor Dripps acknowledged the progress I had made and how my ability to think critically about design had grown, and then added something that has stayed with me ever since:

“Joe, if you want to become a good architect, you must see more good architecture.”

It was a simple point, but a profound one. Experiencing high-quality design first-hand changes how you see proportion, detail, and context. Drawings and photographs can only take you so far. To really understand what makes architecture work, you must walk the streets, study the buildings up close, and feel the spaces.

Following those words of wisdom, we took the same approach with the Celebration builders. After a full day of orientation and discussion, it was time to get out and see some great examples.

The tour was not random. We curated it carefully so the information would unfold in a way that built understanding step by step. We aimed to give the builders a complete picture of what we were trying to achieve, not just in individual homes, but in the entire community.

Most builders were used to thinking about a single house on a single lot. Our focus was different. We were building a place. A great place’s most basic building blocks are the streetscape and public realm. That’s where character, walkability, and community life take shape.

We wanted the builders to experience first-hand the kinds of streets and neighborhoods that formed Celebration’s design DNA, places where architecture, landscape, and public space worked together to create something greater than the sum of their parts.

To encourage cross-discipline communication and help build relationships among the builders, architects, and members of the Celebration team, we assigned seats on the buses. Each builder group was split up, with architects and Celebration team members evenly distributed between the two buses. At every stop, we switched up the seating assignments so people would end up next to someone new. This shifting of who sat next to whom kept the conversations fresh and ensured that everyone had interacted with a broad mix of people by the end of the tour. The goal was simple. We wanted to break down silos, share perspectives, and start building the trust that would be essential once the real work began.

Our first stop was the Old Village of Mount Pleasant, just east of Charleston, is comprised of narrow, tree-lined streets, porches facing the street, and a mix of historic homes and sensitive infill. Then we headed to Beaufort, South Carolina, one of the South’s most intact and livable landmark towns, with compact blocks, centuries-old live oaks, and houses in styles ranging from Federal to Victorian.

As we walked the streets of Mount Pleasant’s Old Village and the historic neighborhoods of Beaufort, we could hear the builders talking among themselves. They admired the architecture and the character of the streetscape, but many said it would be nearly impossible to build houses like these today.

Some pointed out subcontractors and tradespeople might not have the skills to execute the fine details. Others raised concerns about long-term maintenance or warranty issues. We didn’t interrupt or try to convince them otherwise.

We knew what was coming. Less than ten minutes away, just across the Beaufort River, we had arranged for them to see something that would change that conversation entirely.

The surprise was Newpoint, a 54-acre community developed by Vince Graham and Bob Turner. Inspired by the architecture of historic Beaufort’s Old Point neighborhood, which we had just visited, Newpoint broke ground in 1992 and quickly became an important precedent for our work at Celebration. It embodied many of the same urban design principles we were pursuing, and it proved something critical. Newpoint was tangible proof that homes built in traditional architectural styles could meet buyers’ functional needs, appeal to the market, and be delivered at a price point within reach for a large share of buyers.

When our two luxury coaches pulled into Newpoint and stopped at the designated meeting point, Vince and Bob greeted us. Both in their early thirties, they stood casually on the sidewalk, no socks, holding a stack of tri-fold marketing brochures, the kind you might print on a desktop printer. They started with a quick overview of Newpoint’s history, how they launched the project, and the key urban and architectural principles behind it.

As we walked the neighborhood, they pointed out architectural details, explained material choices, and described their design process. It was remarkable to watch the builders’ perceptions shift almost immediately. You could see it on their faces and almost hear them exclaim, “If these two relatively young and less-experienced developers could pull this off, then surely our more seasoned and better-resourced builders could do the same.”

After touring Newpoint, we boarded the buses again and headed to a pig roast at Middleton Place, a national historic landmark along the Ashley River. During the ride and over dinner, we listened to builders and architects trading observations from the day and discussing how they might incorporate what they had seen into the design and construction of Celebration’s homes.

Collaborate: From Ideas to Built Form

With the builders now educated and inspired, it was time to design the houses. A high level of collaboration was essential to do this efficiently and effectively. We had seen on other projects how difficult it can be to persuade builders to change their approach to fit the design vision of a specific development. They were among the industry’s best. Why should they alter what had already made them successful?

Our response to the “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” mentality was simple: one of the biggest obstacles to innovation is success. And, as Bob Stern put it, “It is easier to design in good design than it is to review in good design.” We knew we couldn’t rely solely on the design review process. We needed the builders to work with better designers than they were accustomed to using.

To make that happen, we offered to reimburse part of their design fees if they used one of our preferred architects for the first collection of homes. For the volume builders, this meant their initial set of houses; for the custom builders, it covered their first two.

David Weekley, founder of David Weekley Homes, was the first to take us up on the offer. After spending time with Jim Strickland of Historical Concepts and Carson Looney of Looney Ricks Kiss during our South Carolina tours, he quickly chose them as collaborators.

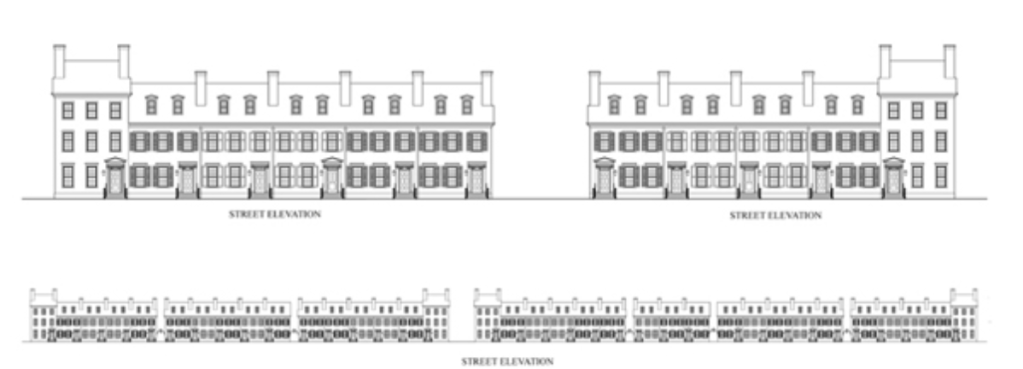

The process unfolded in several steps:

- David Weekley’s in-house design team developed a series of house plans for the Village and Cottage lots, aiming for six plans per lot type.

- Once the floor plans were complete, they sent them to Historical Concepts and Looney Ricks Kiss, who created elevations and roof plans that aligned with the architectural styles in the Celebration Pattern Book. The architects made minor adjustments to the floor plans as needed.

- With this work in hand, the architects and members of the Celebration team traveled to Houston to meet at David Weekley’s offices. Over two days, we pinned every plan and elevation on the conference room wall, debated their merits, and refined them for functionality, aesthetics, and buildability. By the end, the schematic designs for David Weekley’s initial Celebration lineup were complete.

- After the workshop, the architects produced additional sketches of critical details such as wall sections, porch details, cornices, and window trim so David Weekley’s in-house team could get every detail right as they moved into construction documents.

This collaborative effort, combined with David Weekley’s willingness to engage skilled architects fluent in Celebration’s design language, led to:

- A faster design review process

- Early identification of the right vendors and suppliers

- Ample time for value engineering, cost analysis, and construction planning

- Being the first builder to break ground, with enough schedule flexibility to fine-tune construction methods for future homes

- Streetscapes that matched the design vision

- Houses that sold quickly at premium prices

- Multiple design awards

- A reputation that positioned David Weekley Homes as a “go-to” builder for other New Urbanist projects

Town & Country Homes chose not to take advantage of our offer to subsidize design fees if they worked with one of our preferred architects. It would be an understatement to say their design, review, and construction process at Celebration was more difficult than David Weekley’s.

Instead of hiring an architect with the interest, skill, and experience to design homes aligned with Celebration’s vision, they engaged a firm best known for conventional suburban neighborhoods. They worked in isolation, behind closed doors, without early or incremental feedback from our team. There were no orientation sessions to explain the Celebration vision, how to use the Pattern Book, or how the design review process worked.

I later learned that the architectural firm even advised Town & Country’s design and product development team to ignore the Pattern Book, claiming “nobody ever really follows or enforces the guidelines.”

In late December 1995, a FedEx package from Town & Country arrived in my office containing schematic designs for about a dozen houses. We committed to turning reviews around in two weeks or less, so I opened the package immediately. Within minutes of flipping through the plans, I knew I was in for long days and nights. I even considered buying extra red pens for the markups, thinking I might run out of red ink before I finished.

Each design averaged roughly 25 comments, most following the same structure: “The [design component] is inconsistent with the Pattern Book. See Page [Pattern Page Number]. Revise or provide an appropriate historic precedent.”

On New Year’s Eve, I drove to the Orlando Airport FedEx office with a package containing all the marked-up drawings and letters, each stamped “Not Approved” along with the long list of comments.

By January 2nd, Town & Country called in a panic, requesting an emergency meeting to review the feedback. A few days later, we met. Nearly a dozen people attended from their side, including several C-suite executives, their head of design, division president, corporate counsel, and members of the architecture firm. David Pace and I represented the Celebration team.

We started going through the comments one by one. They were direct, objective, and appropriate. Midway through the second house, the Town & Country president stopped and asked his head of design if he had shared the Pattern Book with the architects. The answer was yes. He then turned to the architects and asked why they hadn’t used it. They had no answer, just blank stares.

After that disastrous start, Town & Country finally agreed to our original offer and hired John Reagan Architects, a Columbus, Ohio–based firm known for classically inspired designs and working successfully with residential builders. Town & Country eventually developed a Celebration-appropriate product line thanks to John Reagan’s work and influence.

But the early missteps cost them dearly. Unlike David Weekley, they had no time to build vendor and subcontractor relationships, refine designs through value engineering, or pace their construction to allow for learning curves. They struggled to retain staff, failed to build houses consistent with the approved designs, and suffered significant delays. Homes that should have taken six months to build took nearly a year. Customer satisfaction was extremely low, and the Celebration team had to spend considerable time and political capital on damage control.

Eventually, we decided to remove Town & Country Homes from our builder program and replace them with builders who embraced our vision, worked collaboratively, and delivered results much closer to the success that David Weekley Homes achieved.

Up Next:

In the next article, East Beach: Applying the Playbook, you’ll see how we took these same principles to Norfolk, Virginia — and adapted them for a very different context and set of challenges.

Leave a comment